Rebecca Chew: "I think being an outsider, or having that perspective, helps"

Q&A: An art director on moving from Malaysia to the U.S. for a dream job at the start of the pandemic, the differences in being a creative here and there, and not needing to define home.

However you found your way here, welcome! I’m Emily, and I write letters about how we seek and tell stories to make sense of a changing world and our place in it.

When that Kate Bush song “Running Up That Hill” became popular again after it featured in the fourth season of Stranger Things, I came across a passage in Angela Nagle's Newsletter that made me think of a friend:

Kate Bush has a unique appeal for young people with a gentle outward nature but with a powerful will trapped inside them. She shows them how to direct their will, not into aggressive outward displays of conventional competition, which they are not made for, but into quietly creating something unique.

Possibly, it was because I had recently met her over coffee when she was back in Malaysia for a holiday. (I don’t think I’ve ever told her this, until now—here! in this email Q&A! 😆) But I’ve also long had this impression of her quietly tending to what she loves, when so much in our modern world pushes us to “show” people what we’re working on. It feels like Reb—an art director, designer, and illustrator (who also takes beautiful photographs)—doesn’t often wear her aspirations on her sleeve, preferring to let her work speak for itself when it’s ready.

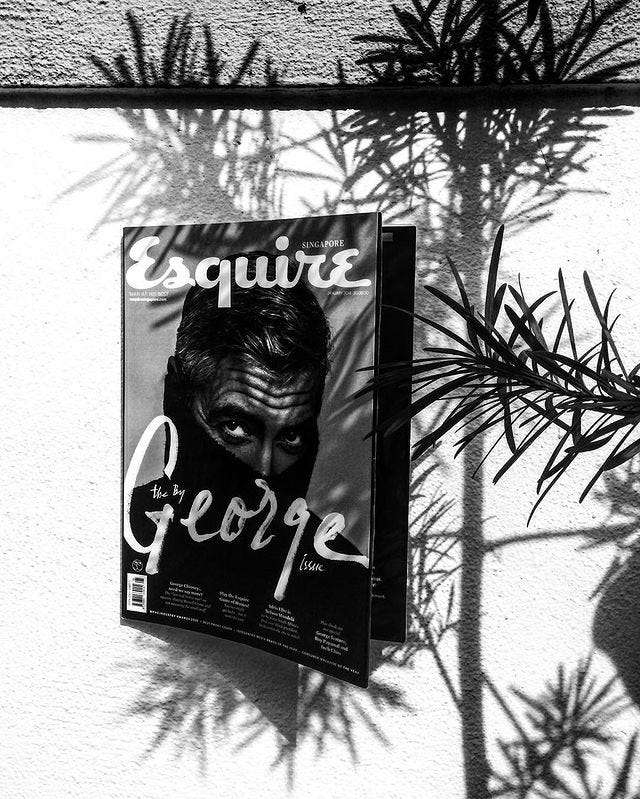

Anyway, Reb and I first met years ago when I joined Esquire Malaysia as associate editor, but she had been the art director of the magazine since its start c. 2011, and also for some years at Esquire Singapore—international editions of Esquire, largely run independently (though content that translated well across cultures was sometimes shared). At the time, the magazine, now defunct, felt like the only publication in Malaysia that really encouraged longform nonfiction (which was what had attracted me); and it was tastefully designed, with an aesthetic that dared to be subtle—thanks to Reb.

Fast forward to around the start of the pandemic: Reb moved from her hometown of Subang in Selangor, Malaysia to San Francisco for a new job at California Sunday—a print magazine known for its narrative journalism and its emphasis on publishing stories from Asia and Latin America. When it folded, she moved to New York as a print art director for the New York Times’ Opinion pages.

That’s not all we’re going to talk about, but things flow from there. I’ll let her tell you the rest ❤️

E.

EMILY DING: So, you made the move to the U.S. at a particularly tricky time—at the start of the pandemic, if I remember correctly? I know it was to start a new job with the magazine California Sunday (I’m gutted that it has ceased publishing!) but can you tell me more about how you got there? I don’t mean the logistical process of getting the job so much as the personal feelings, dreams, or circumstances that led you there. Had you been thinking about it for a while?

REBECCA CHEW: Funny (and sad) that since you reached out, the parent company of California Sunday, Pop-Up Magazine, has also ceased operation. A friend once joked that every magazine I work for is doomed. Apparently I have a proclivity for the doomed. Well, at least I have a track record in something. Anyway. I didn’t intentionally seek to work in the U.S. It’s just that the publications I wanted to work for are based there. After working in publishing for a few years I felt stuck. Not that there aren’t any good writers or editors in Malaysia—we just don’t have the level of support and interest that makes publishing sustainable. I knew there are bigger ideas out there, more demanding standards, and I was hungry to learn and absorb. Working at the New York Times was a pipe dream. So the fact that I’m now working at the Times still surprises and humbles me.

ED: Actually, wait, maybe we should talk about the logistics of migration, if you’re happy to share. Because I think there’s the assumption that if you haven’t already got a permit to work in places like the U.S. or U.K., you would generally be unable to apply for jobs there—especially in the creative industries. Foreign graduates in these countries, after spending all that money going to university, often run out of time to get jobs and switch to work visas there, when their student visas expire. And once they leave the country it’s harder to get back in anew—again, for creative industries. But that’s exactly what you did. You had never studied in the U.S. but you applied, did interviews online, got the job, got the visa. So it’s difficult, but it’s not impossible… Having gone through the process, was there anything that struck you about it—and also, more broadly, about the idea of migrating to “manifest one’s potential”?

RC: I harbored fantasies of studying abroad as a teenager but quickly put that aside when I realized it was not something my family could afford. Because I had neither a foreign education nor a network of contacts that one would have accrued overseas, I had to find another way to work abroad. It required a thick skin, doggedness and necessary naivety. I started applying for publishing jobs in New York early in my career as a graphic designer. It might seem like an ambitious aspiration but I was more motivated by desperation (and unbridled pessimism!) caused by shrinking opportunities in an already unstable industry. I’ve been passed over multiple times until the creative director at California Sunday took a chance on me. I wish the hurdles ended there but the O-1 visa process is dehumanizing as it makes you question your worth. And even after obtaining the visa, your status hinges on you maintaining your worth. And your worth in the case of the O-1 visa is your professional ability. Essentially, you are reduced to utilitarian attributes. Good mental health fodder.

ED: I remember checking in with you a month or two into your move to the U.S., and you didn’t seem entirely convinced by the place and the “competitive”—I think you said?—state of being it kind of forces you into that is very different, I guess, from the general vibe in Malaysia. But you stayed and when I met you again earlier last year, after you had moved from San Francisco to New York, you seemed much more optimistic. There was even an air about you, I felt, that was ever so slightly different! Looser, somehow, in a way that was physically manifest? Is living in New York all they say it is? Or maybe it was just the longer hair, haha.

RC: I think you just caught me in a good mood! I work in the visual side of publishing where there’s this notion of constant productivity. I’m sure you encounter it as a journalist, too. This projection of busyness, of being in demand, through the sharing of work on social media. I’ve consciously (maybe even self-consciously?) tried to not do that as much. And when I moved to the U.S., that hum of productivity felt more heightened especially when creatives here appear less reserved about yoking their identities to their job titles. I’ve always been uneasy about having my job define who I am because it opens up a sinkhole of existential despair. But I’ve since made peace with the fact that everyone struggles with imposter syndrome and I shouldn’t take it so seriously. Self-promotion still makes me cringe but I’m learning that it’s okay to be proud of the work you make. Milestones and achievements are simply things that happen in life, not life itself.

ED: It’s interesting to hear you talk about impostor syndrome because it always felt to me that you’re quietly sure of yourself and what you want to do creatively—like, you’re not going to be swayed by, say, the feedback someone more accoladed has on your art if you don’t agree with it, and you can put it aside to better pursue a kind of “purity” of your own vision. Would you say this is true? If so, how do you think you’ve managed to hold on to that in a world where there’s so much striving for recognition?

RC: I’m a designer, not an artist, so I doubt that what I’m adhering to is artistic purity. Better to call it principles, I guess? While I’m certainly intimidated by some creatives, I don’t have artistic heroes. I know it sounds so cynical but there’s a lot of bullshit and wanking in the industry—self-branding, self-promotion, messiah-complex opining, highfalutin mission statements, etc. I should know because here I am navel-gazing in this Q&A. Always sniff out your own bullshit before anyone crinkles their nose.

ED: What would you say are the differences between being a creative in Malaysia and in the U.S.?

RC: I can only share from my experience working in publishing in Malaysia, and California Sunday and the New York Times in the U.S. I found editors in Malaysia to be less open-minded and the organization hierarchies more rigid. There’s a lot more politicking. Editors and managers prefer designers to stay in their lanes. Designers are treated as decorators and subservient pixel pushers. You aren’t encouraged to ask questions. Maybe it’s partly the fault of the Malaysian education system that the arts or anything artistic is seen as the last resort for those who can’t make it academically. But here, you don’t have to apologize for expressing your point of view because having an opinion is one of the reasons why you’re hired.

ED: Now that you’ve been in the U.S. for a few years, how has that changed your relationship to home? And actually, what was your relationship to Malaysia in the first place?

RC: Home is never a physical place for me. It’s my family and friends. Home is wherever they are. I moved to the U.S. without really knowing anyone, so I am in a sense homeless. I’m still figuring out if New York is my home, but I’m not inclined to define it. I guess I’m more comfortable with that uncertainty now having gone through the pandemic.

ED: Had you been to the U.S. before you moved there? How is social life there different from in Malaysia? Do you find yourself to be different there socially?

RC: In 1994 my dad, a motorcycle enthusiast, won a bike in a contest and sold it off so we could all go on holiday in the U.S. And then in 2007, with more savings, we went on our second family trip, this time for almost a month. We rented a car and made a road trip across several states. We squeezed into motels, took turns under the shower, grew constipated from American food, watched middle-aged Americans tilt their doughy bodies over the rim of the Grand Canyon, and was scandalized by the gaps in restroom stalls. It was great. And then I was in New York for a week when I started at Esquire Malaysia, where in the Hearst Tower, the creative director said I needed to “man up” my designs. Interesting. I also stole a few snapshots of Helen Gurley Brown’s leopard print-carpeted office—10/10 would recommend… And I totally meandered.

Back to the point, I’ve gained a few friends since living in the U.S. I don’t have my closest friends to hang out with on weekends but we still talk every day. I’m naturally an introvert so I mean it when I say I enjoy my own company. I’m comfortable going to gigs and movies on my own. And of course it gets lonely. I’m taking friend requests. Just DM me on IG.

ED: Going back to what the creative director at Hearst said, did you ever feel hamstrung working at a man’s magazine?

RC: I sort of knew what I was getting into when I took the job at Esquire. It was one of the few magazines at the time that was still experimenting with typography and design. It has a rich graphic design history and some of the designers whose work I’m interested in once worked there. But I hated the way women were photographed for the magazine and how men were directed to fuss with their cufflinks as the default “Men’s Magazine” pose. For the first few months, I was the only female staff on the editorial masthead. I wanted Esquire Malaysia to be a smarter, more nuanced magazine. I wanted more white space, I wanted fiction and more long-form pieces, I wanted photo essays. I took it as a challenge and am glad we made a difference, however small or short-lived.

ED: I remember that I looked forward to the box of international Esquire editions arriving in the office every month, so we could see how different countries manifested their magazines in different ways. The perception, performativity, and lived experience of masculinity is obviously different in Malaysia versus the U.S. How would you characterize the differences from your years working at the magazine?

RC: I think Asia is a little more comfortable with androgyny. There are traditional archetypes for sure (i.e., strong, stoic men) but in the media at least, men having delicate features isn’t an indication of eroded masculinity or being less sexually appealing. The American masculine archetype of a gun-toting, whisky-swirling, Hemingway-reading ladies man couldn’t be translated wholesale for the Asian context. That “Esquire man” of the 1960s was dated, misogynistic and would gladly mansplain menstruation. He died of a heart attack at the BBQ pit. The Asian equivalent is probably a Kurosawa lead but he’s not the only representation of manhood. Asia seems less married to a rigid idea of masculinity, or even a singular definition of masculinity. That was what the Hearst CD didn’t understand. I don’t think he anticipated Harry Styles wearing a dress.

ED: Your work—and your Instagram—feels uniquely and subtly informed by an eclectic array of influences that you make your own. I remember one of our ex-colleagues saying, “I wish I could get inside Reb’s head!” What’s one experience that has been most formative for you personally, culturally, artistically?

RC: You don’t want to get inside my head. But seriously, Chungking Express, 1994. I was maybe eight or nine years old. I was a huge Faye Wong fan so I sought out this movie she was in. I didn’t know much about it but after that first viewing on a grainy videotape, I found a language for something I’ve been carrying inside me that I didn’t quite know how to express. That movie opened my eyes to creating stories, framing, aesthetics and music—all filtered through the eyes of a child, of course. I was still chasing ice cream trucks and wearing tattered t-shirts from pasar malam. And then there was this whole world that I couldn’t share with friends because they just didn’t get it. Chungking Express became my gateway drug. It led me to other movies and filmmakers, to music, to books, to art, to photography. It ultimately groomed me into a teenage snob.

ED: I often imagine you tinkering happily in private, ideas filling your head, telling stories by actually making things. Some of the art you created and directed at Esquire Malaysia was very tactile, made by hand, and then photographed or scanned for the printed page… but wait, I’m not exactly sure where this question is going, haha. I think what I want to ask is: what kind of environment is most conducive to your imagination?

RC: I think being an outsider, or having that perspective, helps. Not being truly comfortable in this world can be lonely, unsatisfying and cynical but also unwittingly optimistic because there is hope for an alternative or something better. This is obviously bad for relationships (haha) but probably vital for the creative pursuit. Having the luxury to daydream helps, too. I used to do it a lot more as a child. It appears completely idle to everyone on the outside but there’s a lot of uncensored play going on internally.

ED: Where have you spent most of your life, actually? How would you say the place shaped you—if it did? If it didn’t particularly, why not?

RC: I spent most of my life in Subang Jaya with many trips to Kuala Lumpur on a weekly basis. Subang Jaya is a suburban mall town with horrendous traffic. Growing up, the biggest thing going for it was an ice skating rink in a pyramid-shaped mall. When I was sixteen, Subang felt like a dead-end small town. It still sometimes feels that way but it has a special place in my heart. Deep down I’m really just a suburban kid with a biblical name. Low-brow tastes tickle me, ugliness intrigues me, tacky aesthetics comfort me. My childhood in Subang keeps my feet firmly on earth.

ED: What’s a place in Malaysia you love?

RC: Wandering around Penang at dusk or dawn. Or any small towns in Malaysia, really.

ED: What’s a place in New York you love?

RC: Walking around at dusk, peeking into windows when the lights are turned on. It makes me sound like a total creep but I’m suspicious of anyone who claims they don’t look into people’s homes or are not inclined to peep. Like, aren’t you curious? Sometimes my mind takes over and I start imagining stories, the windows as frames where movies play out. I wonder about the people who exist in these rooms. There’s a certain Hopper-esque melancholy in this act that fills me with existential loneliness but it also strangely calms me.

Views and experiences related are the speaker’s own. Guest appearances here hope to reflect the variety of life in this world.Reb’s three good things

Aftersun: So gentle and heartbreaking. The performances and framing, the 90s childhood redolent of chlorine and sunscreen. I soaked this movie in. One of the best things I’ve seen last year.

Self-Help by Lorrie Moore, or anything by her tbh: I’m a huge fan of her sense of humor and the way her characters view the world. Very few writers make me LOL. Lorrie Moore is one of them. And when you don’t see it coming, she wrecks your heart and leaves you bereft.

Stay True by Hua Hsu: At the risk of sounding earnest, this book made me ugly cry. This is for the awkward music-obsessed teenager in me.