Watching Gaza, still...

...while enjoying the summer in Berlin, the discombobulation of it. (Plus: glimpses of the distorted 'economy' in Gaza.)

However you arrived here, welcome. I’m Emily, and I write letters about trying to make sense of a changing world and our place in it.

“Don’t feel sorry for us. Feel sorry for yourselves, that you’re living in a country that is arming Israel, that is sending weapons overseas to kill children. Your bombs are killing children. If that bothers you, then don’t feel sorry for us. Feel sorry for yourself. That you don’t have enough say in your own country to stop it.”

—Noor Alsaqaa, communications officer for Doctors Without Borders in Gaza

A journal entry from mid-August:

One thing I’ve really been enjoying in Berlin over the summer is taking a picnic mat out to a park and stretching out to read—some days, I managed to read an entire book, cover to cover. We would pack drinks and snacks from home or buy them from a cafe nearby. It’s a ritual I’ve come to relish reliably, when I want some solitude but also wish to be out in the world at the same time, when I want to enjoy the full bask of sunlight that our hinterhaus ground-floor flat circumscribes, when I want to give myself over to a book and enjoy it for what it is, not try to study it at my desk. Occasionally, while I’m doing this, I’ll check my phone, and something about the atrocities being done to Palestinians by Israel but also by the world, the sheer injustice of their condition, will impress itself, and my helpless complicity, onto me. I will think about how even the most everyday of pleasures, like sitting somewhere among people going about their day, breathing in the air and the light in a moment of peace, has been made impossible in Gaza. Did you see how the Israeli government attempted to ban Gazans from their sea shore, from something so primordial as nature? Did you see how, as Bisan Owda showed, they refused to listen, defiantly fought for whatever morsel of joy they could get for themselves? It makes me think that there can be no shame in grasping for joy wherever one can find it—what does one gain from withholding it from oneself, after all? But even while I think it, try to apply it to myself, to the rest of us, it can’t help but feel false. Life goes on, for the most of us. Aside from the truly brave and hopeful—those who protest consistently, who risk their lives to join the flotillas, who speak out no matter what pressure they’re under—most of us continue with our lives as we always have. But does one have a right to just continue living one’s life, to enjoy it, in times like this when the world is turned on its head? Is it enough to join the odd protest and donate and boycott and speak out and still go for weddings and birthday parties and holidays and laugh and clink glasses and pay mostly lip service to Gaza in broader company? Is it enough to just be constantly aware and thankful, to remember that there are others who have no right to do the same, have had that right snatched away, and to do whatever is within one’s capacities to try to change things? How much disruption to life-as-usual is one obligated to inflict, on oneself and on others, in order to make the world right again? Does truly being in solidarity mean also going on hunger strike, as a Palestinian trio of journalists did and asked the world to do—but nobody responded in kind, and who can fault them? For those of us who do not ourselves face extinction, a hunger strike must seem the height of nihilism, not indomitable hope. For those of us who still have safe harbour in this often pitiless world, a hunger strike must seem the act of someone so desperate they have no other recourse, because what does going on hunger strike even mean if one isn’t prepared to die? (Fasting is, of course, a different proposition.) That’s the difference, isn’t it? We are not the ones suffering. Our loved ones are still alive, not bombed to bits and rags; they still have a lot to live for, we still have them to live for. Outside Gaza, outside the world’s conflict zones, the world still looks beautiful. If you look away long enough (easy, just click off your screen), keep the violence at bay long enough, the world remains beautiful. And you’ll feel good, and you’ll feel wicked, all at the same time. But who cares, really, how you merely feel?

Some reading notes on Palestine:

1./ A piece I read in the summer 2025 issue of The Berlin Review features an insightful essay by Tash Aw, for which I bought the hard copy—but it’s also notable for the diaristic piece by Nahil Mohana, “The Price of a Watermelon” (translated by Katherine Halls), which provides an insight into the broken-down ‘economy’ of Gaza:

Summer is barely here yet, and the price of a watermelon is 70 shekels. That’s 19 dollars. The war has divided people into two groups: business owners who gobble up money and hoard cash, and the rest of us, who face a constant, humiliating struggle to obtain hard currency. I rely as far as possible on a banking app that allows me to transfer funds directly to a beneficiary’s account, though it requires an internet connection to function. Many shops, businesses, and even stalls in the street use this method because there’s so little cash to be had. Employees receive their salaries through the app; the alternative is to withdraw it in cash from an exchange service, but commission these days can run to 35% or more, meaning that for every 100 shekels you withdraw, you lose 35. And that’s if you can find a bureau in the first place.

The other day, my 14-year-old daughter told me she was craving a crêpe with Nutella. A friend of hers whose father runs a business eats crêpes with Nutella every day, she told me. It’s exam season at the moment, and I want her to have everything she wishes for while she’s busy revising, including the sugar rush of a Nutella crêpe, but the owner of the sweet shop can’t be convinced. He’s insisting he can only take cash for the portion of crêpes I order in advance by phone, which, by the way, costs 70 shekels.

I put the phone down, furious. Then I do something rash. I order 300 shekels—83 dollars—worth of crêpes and other sweets from the other confectionery shop, which does accept app payment, just to spite anyone who makes me feel like I don’t have any agency. It’s a little victory for my own humanity.

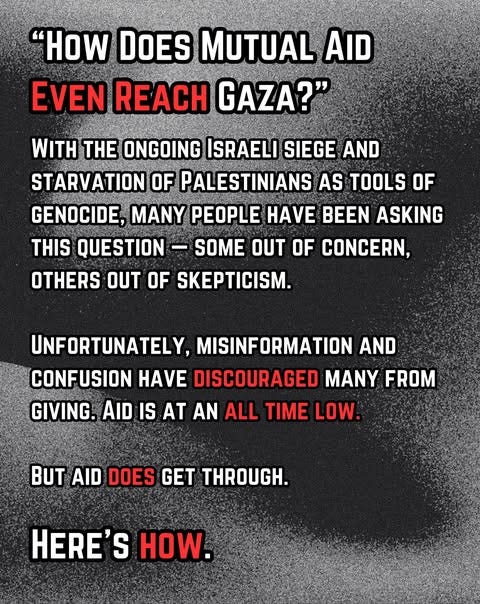

2./ This Insta post (read the caption) I found speaks to this matter too, in response to people who want to donate to Gazans but understandably ask how money donations can possibly help them at this time when Israel is preventing food and urgent aid supplies from getting to them:

World Central Kitchen and Red Cross UK also have updated FAQs on whether aid is getting into Gaza, and if so, how.

3./ Recently, Al Jazeera published a piece about Israel blocking the transfer of currency to Gaza:

Civil servants have gone months without pay. NGOs are unable to transfer salaries to their employees. Families cannot send remittances. What once supported Gaza’s financial structure has vanished. There is no mention of when it will return. Just silence.

Money is stuck. Trapped behind closed systems and political barriers.

If you manage to obtain money from outside sources — perhaps from a cousin in Ramallah or a sibling in Egypt — it comes at a cost. A brutal one. If you get sent 1,000 shekels ($300), the agent will hand you 500. That’s right, the commission rate on cash withdrawals in Gaza is now 50 percent.

There are no banks to offer such withdrawals or oversee transfers.

The signs are still there. Bank of Palestine. Cairo Amman Bank. Al Quds Bank. But the doors are shut, the windows are dusty, and the inside is empty. No ATMs work.

There are only brokers, some with connections to the black market and smugglers, who are somehow able to obtain cash. They take huge cuts to dispense it, in exchange for a bank transfer to their accounts.

Every withdrawal feels like theft disguised as a transaction. Even so, people continue to use this system. They have no choice.

Do you have a bank card? Great. Try using it?

There is no power. There’s no internet. No POS machines. When you show your card to a seller, they shake their head.

4./ From a 2024 essay by Mosab Abu Toha:

on social media, Hamza posted a photograph of what he was eating that day: a ragged brown morsel, seared black on one side and flecked with grainy bits. “This is the wondrous thing we call ‘bread’—a mixture of rabbit, donkey, and pigeon feed,” Hamza wrote in Arabic. “There is nothing good about it except that it fills our bellies. It is impossible to stuff it with other foods, or even break it except by biting down hard with one’s teeth.”

5./ I’ve found the newsletter of Alaa Radwan to be a thoughtful read. She’s a Gazan writer, translator, and educator who managed to evacuate to Cairo in May 2024 and is now teaching Arabic classes for beginners online. Interestingly, she is also, with a team of Gazans in Cairo, translating a Syrian TV series that tells the story of Palestine between 1933 and 1976 in honour of her late university professor.

Here’s a passage from one of her letters, published in July:

This war has redrawn every line. The slogans no longer matter. The rhetoric has lost its power. Al-Aqsa, Jerusalem, and liberation have become distant words. The people are not dying for symbols. They are dying for survival. And even that seems out of reach. They are dying for flour. Not luxury. Not comfort. Just flour. Just bread to silence the hunger in their children’s stomachs. This is what the war has reduced them to.

My brother Yahya, 28 years old, told me recently that he felt victorious when he managed to get a bag of flour from a truck before it was looted by armed gangs. That is what victory looks like today in Gaza. Not military gains. Not diplomatic wins. Not symbolic speeches. A bag of flour. That is the scale of hope we are working with now.

More thoughts from my journal, written mid-August: