Mabel Ho: “I still flirt with the idea of leaving. But that dream plays to a different tune now.”

Guest letter: After years imagining what her exit plan would look like, a Malaysian finally comes to terms with her choice to remain.

However you found your way here, welcome! I’m Emily, and I write letters about how we seek and tell stories to make sense of a changing world and our place in it.

You’re about to read a guest letter from Mae, whom I’ve known since we were teenagers, though we’ve gotten to know each other better in recent years. We’ve often found common ground in books and writing and freelancing and despairing about not getting through an over-ambitious to-do list because we weren’t sure which task to prioritize first 😅 We’ve also shared a perennial unsettledness, though every person’s experience of it—what drives the feeling and what they are looking for—is, of course, different.

When I saw an Instagram Story she posted about volunteering as a polling/counting agent for Malaysia’s general elections last November, and how she was compelled to do it because she wanted to belong more to Malaysia, our home country—a feeling that had for so long eluded her—I felt that the sentiment it encapsulated fit right in with Movable Worlds, and asked if she would like to explore it further in a guest letter.

Here’s what she wrote, which I found to be frank and moving—critical, but also filled with love. It comes at a particularly good time, since Michelle Yeoh’s recent success has ignited the debate again among Malaysians on whether one has to leave the country in order to make it. Enjoy reading, and feel free to share your thoughts with her in the comments, or hit reply and I’ll pass it on.

If you have a story you would like to write and share on Movable Worlds too, please pitch it here. Feel free to also send it on spec. The fee is USD$150 per letter and I promise it’ll be a collaborative process ❤️

E.

A letter from Kuala Lumpur by Mabel Ho

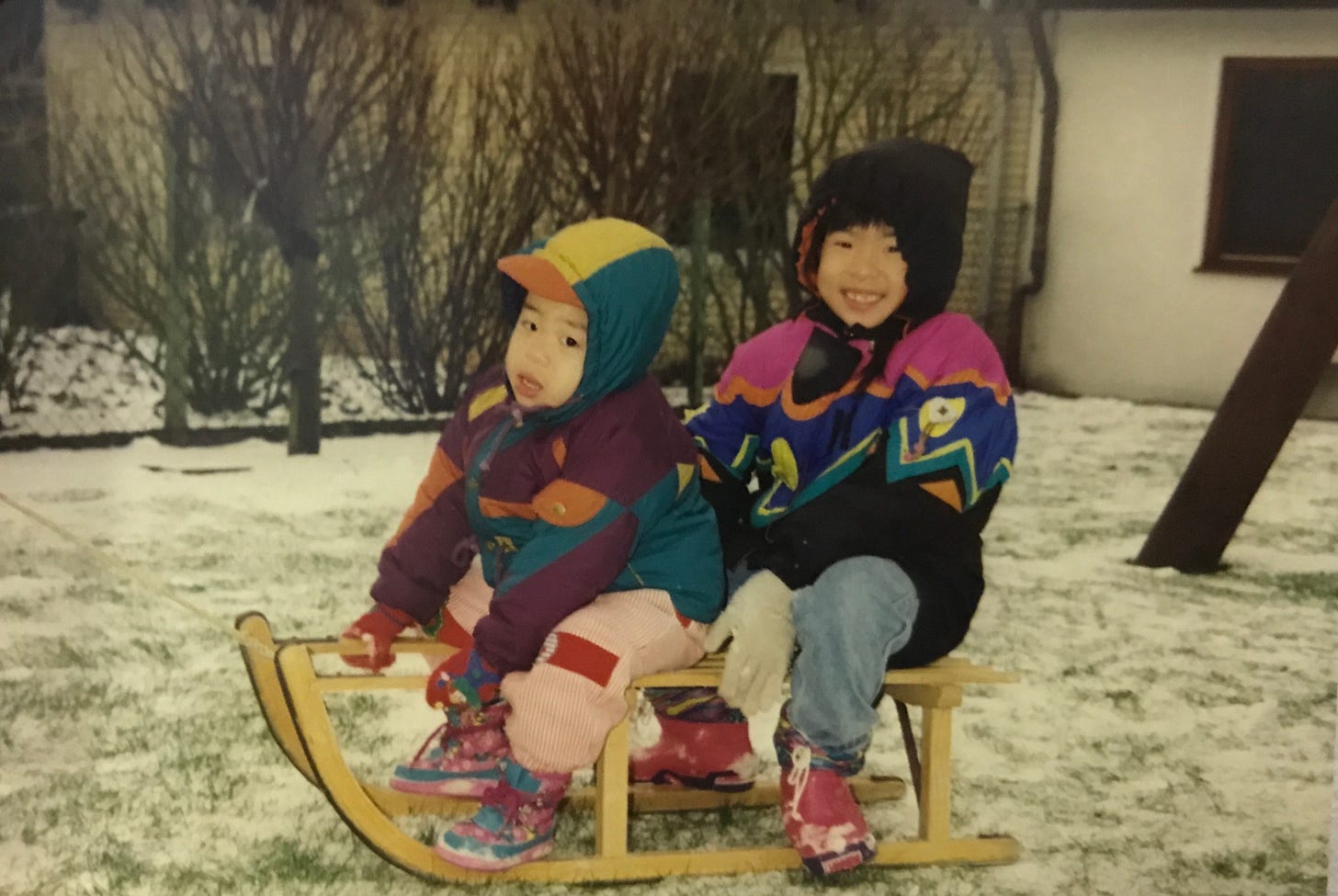

Photographs provided by the writer

Mabel Ho is a writer and reader—learning, feeling, and listening her way through life in Kuala Lumpur. She writes at maemoji.substack.com, where she hopes to start publishing regularly soon. (It has been three years!)Days after Malaysia’s fifteenth general election last November, my country was still at a political stalemate. There was no clear winner and we had a hung parliament. Confusingly, both the heads of the two coalitions leading the race were saying they had the numbers.

Memes about how Malaysians were incapable of getting any work done flooded social media as we waited. It was impossible to concentrate on anything else, so I joined the masses refreshing Twitter and Malaysiakini every few minutes. I watched explainer videos from rebel activists and Tiktok pundits like Kuasasiswa and Iqtobal on Malaysia’s democratic and political processes: what contingencies would kick in if this or that happened, or if the impasse persisted.

I needed the political education. Despite growing up in Malaysia—I left when I was fifteen to study in Australia—I had always felt insulated from it. While I carry a Malaysian passport, I had no clue what it meant or what it had to offer me. Why did I have to know, if I was brought up on the notion that I was always meant to migrate elsewhere? Even when I came back as an adult in my mid-twenties, I felt much the same, thinking my return was temporary.

All my years here, I had often asked myself, What is this bubble I live in? But I never arrived at a satisfying answer. Now, having fashioned a semblance of a life here over the past decade, I thought it was time to unravel the complexities of my relationship with my country. I wanted to see more of it, understand it better, just be a part of it more—but on my own terms, not my parents’.

One thing I decided to do was to participate more actively in the democratic process. This is, after, all, the only country in which I have the right to vote. So during the general election, I signed up as a PACA—polling agent/counting agent—who volunteers on behalf of a political candidate to observe the polling and voting processes at a particular constituency on election day.

Yet, I was padding what I was doing with caveats. “I’m not doing this for the country. It’s for my own selfish reasons to understand more about things I clearly do not know,” I told my friends. “Being Malaysian, for me, has felt like being married to someone you don’t know.”

This knee-jerk reaction, lest I appear a blind patriot, gave me pause. Why was I so quick to reject Malaysia? The disconnect felt discomfiting. I knew I had to stop being forever angry and resentful, but why were those the only feelings I had ever really felt for my country? I can’t keep worrying over the same old wounds. At the same time, I thought that Malaysia, too, had to stop being forever angry and resentful, if there was to be any hope for political change.

For a long time, I was hesitant to say that I was Malaysian when I was abroad. I felt a sense of embarrassment that I was not “Malaysian” enough.

I felt that way for various reasons, but in large part because English is my first language and I am unable to speak the Malay language properly, and I often felt the need to justify why I have an accent that apparently sounds American. I know how it made me look when I offered up half answers as reasons, though they’re all true.

—“A big portion of my mom’s side of the family lives in America, and we used to go there a lot.”

—“Hollywood and TV, you know.”

—“I don’t know, I’ve just always spoken this way.”

I grew up speaking English with my family. And even though I had gone to a school that put me through the local education system and structure, where I learnt Malay as its own subject as well as the teaching medium for other subjects, I still had no real grasp of the language. My peers all spoke English. Most of our teachers spoke to us in English. A fair number of my country’s mainstream news media are in English. All the books and movies and culture I consumed were in English. All this oriented me, for the longest time, to always look outward.

When I returned to Malaysia in 2012, I remained steadfast to the idea that I was still only in transit. My shipped boxes home remained unopened, just in case I was to move somewhere else again. I became accustomed to fielding questions about when I was going to leave next.

It would be tempting but dishonest to say that I felt I didn’t belong in Malaysia because it had rejected me, somehow, because it wasn’t the country I wished it to be. There is widespread corruption, racialised policies, and a lack of freedom of speech, among other issues. But I see now, with the gift of maturity and time, that I had it on backwards. The obnoxious truth was: I did not want to fit in. I had it in my head that Malaysia was not suited for me, I was the one doing the rejecting.

I can only wince now at the audacity of my younger self. I want to deny that I had ever uttered these thoughts out loud.

Every new place I imagined moving to felt like an escape hatch, but what I told myself about what I was reaching for and why I was reaching for it started to feel disingenuous. I mean, what was I running from? I had a very sheltered upbringing, one removed from most of the people who make up this country. I was educated in a private school, and the people I grew up around had the privilege of not having to depend on public services. The idea of leaving began to feel like a marketing ploy: romantic notions upon which I rested my ambitions—surely a mere impression of what my new life could be. These delusions of grandeur meant that I was always halfway checked out of my life in Kuala Lumpur.

That went on for six years before I conceded, finally, to unpack those boxes. Until a couple of years ago, I was still building my exit plan from Malaysia.

As a PACA, all that was required of me was to sit at my assigned polling station and watch for discrepancies and to ensure that the electoral officials were carrying out their duties fairly. On November 19, we carried these out in shifts, and due to a shortage of volunteers, I had to do a six-hour run—four hours observing the polling process, two hours observing the counting of votes.

I volunteered for Gobind Singh Deo, the Democratic Action Party candidate for Damansara, and honestly, I had no idea what his policies were at the outset. I just knew that I wanted to do it for an opposition party, and that they needed people—which was reason enough for me. The Damansara constituency is large, with almost 240,000 voters, and he ended up winning by a six-figure majority so there was no real contest, not much room for dispute. The leader at my polling station was a firm but kind lady—I think she was a teacher, as voting is often done in schools, where teachers are tasked with administering the process—and if I felt out of my element, she put me at ease.

Nevertheless, I was still anxious the night before, particularly about the possibility of having to use any of my atrocious Malay. For most of my shift, I was seated next to a PACA from another party who was extremely chatty with me—in Malay. Eight years younger than me, he had PACA-ed many times before. He talked about being in gang fights, having a gun licence, and being a freelance bodyguard for rich men’s children. Were it not for the language barrier, I would have liked to ask him more. He’s not someone I would usually meet among my circles of friends. What kind of Malaysia has he known?

Anyway, a PACA stint is just that—a stint. It’s not like it changed my views or feelings about Malaysia overnight. I think I had hoped to feel inspired by doing it, though I can’t say that I necessarily was. But I did feel like an active participant in the process of choosing, in a little way, the Malaysia I want to live in. I was wading in, finally, now that I am living here—not somewhere else.

My parents couldn’t understand why I was doing what I was doing. They didn’t even know what a PACA was. When they found out, they looked at me, bewildered. But why? they asked. Evidently, my oblivion and naivete to this country didn’t come from nowhere. I just had to look at my parents’ own relationship to Malaysia.

I grew up with the understanding that I was always meant to leave Malaysia. Heavily influenced by my mother’s side of the family, half of which is based in the U.S., the dream was always to leave for more “Westernised” countries, for bigger economies, for supposedly greater freedoms. Even if one were to move just across the causeway to Singapore, that would be better than nothing. My parents had essentially placed all their focus on making my brother and I leave. (He did.)

In the days after the election, before the long-suffering Anwar Ibrahim was finally confirmed as Malaysia’s new prime minister on November 24, I learnt more about the history of Malaysia through this Malaysiakini story on the spectre of May 13. It was published in 2019, on the fiftieth anniversary of the violent racial riots which were taught to us as Malaysia’s darkest episode of history.

As I read more, I learnt that the riots in Kuala Lumpur and its surrounding areas were triggered by the upheaval of the 1969 general election, leading to a reconfiguring of the political landscape and a hung assembly in the state of Selangor. I felt my cheeks burn with mortification. I had known about the riots, but I hadn’t known what had led to them. It seemed like stories about the riots were making the rounds again because the present election had resulted in similar upheaval—a hung parliament for the first time in Malaysia’s history.

My mother’s side of the family had grown up in the district of Petaling Jaya in the state of Selangor, so they would have been close to where the riots were. My mother was thirteen years old at the time, home alone with her four sisters and her mother. She saw military tanks on the street, was afraid to walk to school. My youngest aunt was only eight months old, still being fed formula milk. My grandfather was away on business in Penang and could not make it back due to the public emergency that had been proclaimed. These were the stories fed to me growing up. It was the fear that had made an impression on them, and on me.

My maternal family’s WhatsApp group chat had been pinging with messages throughout the elections. Only three of us still lived in Malaysia: my mother, my aunt, and me—the rest of the messages were coming in from other parts of the world. But my relatives abroad continued, as they always had, to share anecdotes and outdated information about Malaysia, in a way that I felt to be glib. When talk of the riots came up, the assumption was mostly that they were caused by the Malays. “Nothing to do with us what!” they said.

Hoping to inspire some dialogue with my family, I shared the Malaysiakini story and marvelled at how I had not known such an important piece of our historical puzzle. I asked if they had known, but I was met with total silence. Then I was blue-ticked. Nobody seemed to want to engage.

A few hours later, my mother texted: “Happy Thanksgiving Day everyone!”

I stared at my phone in disbelief, feeling suddenly overwhelmed by the chasm between us. I pinged her privately: “Mom, we are not American, why you go and say this??”

“Well it’s still Thanksgiving day, celebrate or not.”

My paternal grandparents were the first on my father’s side of the family to arrive in what was then Malaya. They came from Guangzhou as married young adults, and focused all their energy on surviving in their new country, hoping for a better life. But Malaysia then is not Malaysia now, and my grandparents rarely went outside their community. They only spoke Hakka, and regarded other races with some wariness.

My father, too, seems to have a fractured sense of identity in relation to Malaysia. At one point, he talked often about leaving Malaysia to live out the rest of his days in Lijiang, a part of China he has never been to. He almost exclusively consumes China-based media, so much so that I’ll often jokingly ask him, “What are you watching, Dad? Propaganda?” And whenever I visit my parents and ask him what he’s been reading, he’ll quip, “More propaganda.”

I don’t think my father feels that he belongs in Malaysia, but he also has nowhere else to go. His parents came from China, but he has no real ties to it.

In a way, his fumbling search mirrors my search, except that I have the benefit of at least another thirty years to build a life. He has already built his life—it’s right here, but he can’t live in it fully. And I wonder if holding on to the dream of somewhere else is the only way he knows how to deal with his disconnect.

I used to think that I had to choose the country that would offer me the best way forward. But I’ve realised I no longer need that certainty—and Malaysia’s path forward is yet uncertain. It’s enough for now that I am where I choose to be, and that I make the most of it. In looking a little more beyond myself and whatever disappointments I may have felt in my life, I’ve begun to appreciate things I hadn’t appreciated before.

Because what this country lacks in good governance, we make up for it with kindness in spades. I’ve learnt over and over that every Malaysian’s coping mechanism in times of crisis is a generous sense of community, with a healthy dose of memes and dad jokes. The pandemic grounded me, both literally and metaphorically, in witnessing how people came together. #KitaJagaKita (“we take care of us”) started as a grassroots effort on social media, matching those who could help with those who needed help. This continued when floods ruined the homes and livelihoods of Malaysians in December 2021, and many who were able jumped right in to lend a hand with the clean up.

I’ve even come to appreciate how we Malaysians don’t try to be anything we’re not. If we’re mediocre in something by some put-upon external measure, we learn to contend with it in our own ways. Maybe some of us are too mild-mannered for the kind of forging ambition we’re supposed to want; or maybe call it age, because I’ve become less intense myself.

But though life may feel smaller here, in a country that rarely figures on the world stage—unless, it seems, one goes abroad and succeeds, like Michelle Yeoh—it isn’t any less gratifying. There are many little things I love about living here: the year-round sunshine (something I used to hate growing up, especially after experiencing the changing seasons overseas), the random food stalls cropping up at the side of the road at all hours, the community of friends and chosen family I’ve come to build. I’ve been able to spend a lot more time with my parents and Fitzy (Fitzgerald), my miniature schnauzer, who takes up a large chunk of my phone’s camera roll. Life is chill. I’m learning to cherish what we have and what we are—and what I have and what I am—instead of picking constantly on what we are lacking.

It was completely understood that I was not meant to stay, and I wouldn’t have to explain myself if I decided to leave tomorrow. But I find myself stuttering justifications for having remained here. There is no neat story; it comes out in a tangle of defences and validations. The simple answer now is just: I want to. Although my life here doesn’t look like how I envisioned when I was younger, Malaysia is the only place in the world that has afforded me the space and time to feel my way around and find my life’s contours—eventually.

I’ll admit that sometimes, when aspects of life here frustrate me, I still flirt with the idea of leaving. But that dream plays to a different tune now. If I were ever to leave, I wouldn’t be running away or looking back in disdain. I would be excited to go, and I would also be excited to come back. It most definitely would not be an exit plan.

Views and experiences related are the writer’s own. Guest appearances here hope to reflect the variety of life in this world.