Kaori Fujimoto: What we give when we give money to the dead

Guest essay: A Japanese essayist on negotiating deep-rooted traditions and her own wayward path, and how this shaped her relationship with her father.

Hello again, friends and readers!

You might have noticed that I didn’t end up sending out a guest letter last month, since I wrote one of my own. This time, I’m happy to share something with you by Kaori Fujimoto, whom I first met at a writing workshop many years ago. In the intervening years, we’ve exchanged messages about writing and reading, and visited each other’s countries for the first time. The experience of seeing someone you know from another place in a place you’ve never imagined them before is a very particular kind of joy—a way of collapsing time.

When I reached out to Kaori about writing for this newsletter, I was thinking about the mixed feelings she had shared with me before about being a woman in Japan—a country with traditions so distinctively beautiful but also, for some, confining. When I approach someone to write here, I often have something in mind from what I already know of them, but I always let them know to disregard my suggestion if I’ve somehow misunderstood the import of something or if it doesn’t feel meaningful enough to write about. I make sure to let them know that they should feel free to explore without any particular “message” in mind or any contrivance of connection to place, though they would use the idea of place as a starting point.

As it turned out, Kaori wrote back saying she might have something along the lines I was thinking of—“The idea of writing about condolence money had been hovering in my mind for years,” she said—and she let it go where it wanted to go. This is the result. If you enjoy reading it, give it a ❤️, leave a comment, or share it. Many thanks!

Don’t forget that you can catch up on all past guest letters here. If you’re interested in writing one too, please reach out.

A guest letter by Kaori Fujimoto

All photographs provided by the writer unless noted otherwise

Kaori Fujimoto is an essayist from the greater Tokyo area, where she also currently resides. Her writing has appeared in the Common, Literary Hub, the Threepenny Review, Mslexia, and other literary journals and anthologies, and been listed as Notable in The Best American Essays. To read more of her work, try “Shinjuku Golden Gai and the Midnight Diner” and “Embracing Imperfection: On Writing in a Second Language”.A letter carrier delivered another batch of registered mail envelopes filled with cash to my parents’ house. My mother and sisters counted the money and jotted down the senders’ names and the amounts before placing the envelopes on the Buddhist altar, in front of which my father’s body lay.

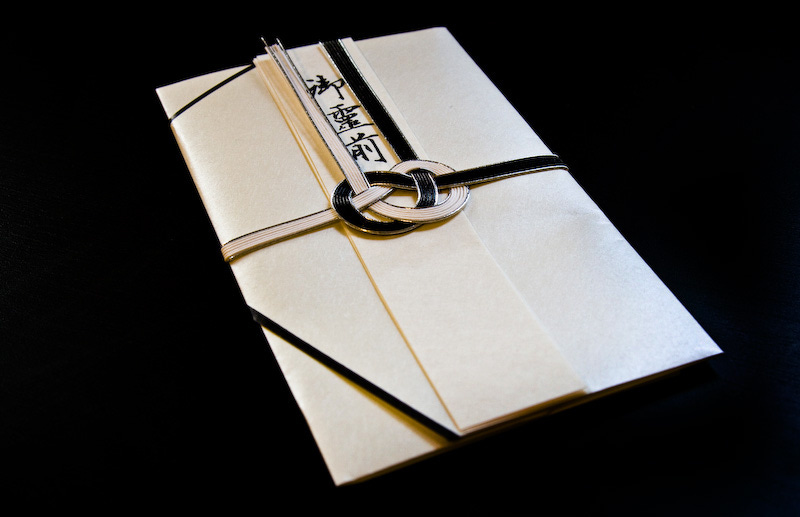

Money had been rolling in since his passing—condolence money, or kōden in Japanese, literally meaning “offering of incense”. It came from family and friends, who were unable to attend the wake or funeral in the countryside where my parents had lived since retirement. The accompanying messages read: “It breaks my heart to think about the grief your family is going through,” or “This is a small amount, but please spend this on incense.” They all sounded similar, some almost exactly the same, as many were traditional stock phrases. Nevertheless, these notes seemed better than no message at all.

Kōden also follows long-standing rules: Never use crisp bills. Place the money in a special condolence envelope according to specific instructions, such as that the front of the banknotes must face the back of the envelope that must be closed also in a specific way. The amount to offer depends on the sender’s relationship with the deceased. So, my siblings exclaimed when our father’s distant friend sent 50,000 yen (about 500 dollars), though 5,000 yen would have been enough, and when a close relative, whom our father had helped many times, sent only 10,000 yen, though 30,000 yen would have been more appropriate. After the funeral, the senders would receive gifts in return that would be worth half the value of their kōden. My family, just as other families, would commission this overwhelming task to a department store after other daunting tasks for the funeral. “What people say is true—the bereaved have no time to grieve!” one of my sisters said.

I made no comment. I was not in charge of the family’s practical matters, especially when they involved handling traditional protocols, which I hadn’t bothered to master. I didn’t understand their point. These formalities often require that only cash be given, for both funerals and weddings, and the rules that apply significantly differ according to the type of occasion. Why won’t gifts do? Why the detailed rules? Why does everyone follow them blindly?

I’d long considered myself lucky that in my family, it was my older siblings who helped our parents take care of such customs. In any of the offices where I’d worked, I also escaped a permanent employee’s obligations to attend coworkers’ weddings and to be involved in other office customs, including periodical after-hour socials. I temped as a business translator, moving from office to office—bank, law firm, IT company, ad agency, among others—before becoming a full-time freelancer.

“Working for different places must never bore you. That may be good,” my father once said. This was the first time he had shown approval for the way I worked. In a country where most university students are expected to secure employment in their graduating year—in recent times, it’s been reported that at least ninety-six percent do every year—my refusal to stay on the payroll of one company had maddened him.

Understandably, he wanted his daughter with university degrees to follow the usual course of decent job, marriage, motherhood. But my priority was to become a writer and versatile translator, rather than a wife and mother. I’ve loved reading and writing for as long as I can remember, and I am fully in my element when I work with words. I’ve chosen business translation as my day job for the challenge of rendering different types of Japanese texts into English and because it lets me engage in the act of writing all day, learning new words and constructions I could use for my own writing.

My father often sighed at my non-permanent employment status, yet he also understood my craftsman’s temperament and inability to cleave myself to an organization, because I inherited these qualities from him. He was a self-employed architect with a first-class license. He prided himself on his skills and knew it would take grit to work for different clients with no job security. So, eventually, he accepted my choice.

#“Kaori, are these your friends?” My mother showed me the senders’ names on three envelopes.

“Yes,” I said, and read the enclosed condolence messages. They were from high school friends who had met my father only briefly. Two days before, on the night he died, they had texted me wishes for the New Year. When I told them the news, they immediately phoned for my parents’ mailing address so they could send kōden.

“I didn’t let you know to solicit kōden,” I said, astonished. “You hardly knew him, so don’t do anything.”

“I won’t not do anything,” they all responded. “This is the only thing I can do for you now, so let me do it.”

Despite having small children at home, they each made the effort to buy a special envelope, handwrite their messages, and travel to the post office the next day.

In high school, these women effortlessly blended in with classmates and thrived in school activities, while I never fit in—I just couldn’t enjoy my schoolmates’ company or group activities, and it showed in the way I carried myself. After high school, these women followed the course my parents had wanted me to follow. Yet, they were among the few people I knew who didn’t dismiss me for frequently changing jobs, for dating men I never considered marrying, and for being ill-equipped with the intricacies of Japanese social etiquette.

“You shouldn’t have a life like mine, Kaori. If you did, that would make you a person who’s not you,” one of them once said. How I wished my family members understood me the way she did.

But my father might have, albeit vaguely.

My parents moved out of the greater Tokyo area when I was in my mid-thirties. When I visited them in their provincial town, my father and I often traveled to a grocery store in his car. Once, on a sunny autumn’s day, as we drove past vacant lots overgrown with tall grass, I asked him to pull over so I could get out and take some photos. The sepia grass swayed and rustled in the breeze, and I felt compelled to photograph them in the soft, bright light.

After snapping a few pictures, I just stood there in the quiet of the sun-filled field, comforted, but also dispirited. At the time, I was in a limbo of staying put—in a job and a relationship I had temporarily settled for, and in a state where I read and wrote as an aspiring writer with no prospects of publication. I had no idea where I was going, where I would be happy—if I would ever be happy.

I turned around and saw my father watching me. The apprehensive look in his eyes told me he sensed my predicament.

A condolence telegram from another friend arrived two days after the kōden from my three friends, one day before the funeral. Kōden was not enclosed. She was my oldest friend and had talked to my father numerous times. The telegram did not offer any conventional phrases of comfort. She wrote about how glad she was when my father looked after her little daughter’s goldfish when they were away on a family vacation. The whole message sounded like one written by an elementary schooler.

When I’d called her to let her know about his passing, I said she wouldn’t need to do anything, just as I did with the other women, and I meant it. Yet, after receiving the kōden my other friends sent, despite my resistance and all the trouble they clearly had to take, I felt offended by one childish telegram sent so late—particularly because I knew she was a penny pincher.

I sat by my father’s body in front of the Buddhist altar that had been assembled by two men from the undertaker’s. Receiving our call late at night, they came to the hospital in black suits and ties, transported his body to this house, and put up the altar with incredible swiftness. Both of them were respectful and thoughtful while they worked out the details of the wake and funeral for us, which moved me. Money and messages piled up on the altar.

I had always regarded Japan’s traditions as shackles. But, going through all this, I began to understand that strict adherence to some formalities is the best and easiest way to show care and respect, especially on the occasion of a loved one’s death, when there is little you can do to blunt the pain of grieving.

“Holy cow, you’re impressive,” my father had said to me when an article I wrote was accepted by a British magazine, and when I was selected as a fellow for a creative writing workshop in Europe. His compliment surprised me more than it delighted me at the time. Now, after his death, the value of the words finally sank in, with the weight of the knowledge that he had truly meant it.

His body would be transferred to a coffin for the funeral the following day, and we would fill it with flowers. We asked the undertaker to prepare jolly, brilliantly colored flowers. We knew he’d hate typical funeral flowers like chrysanthemums. He was an offbeat fellow in many ways. He disliked most of the conventions he had to handle as the head of the family, but adhered to them anyway.

“You never listen to me,” he often said.

“I’ll continue to not listen to you,” I thought by the altar. I had bucked everything he expected of me as a Japanese woman, trying to carve out my own happy place in a homeland where I found it difficult to be happy, partly because of the traditions I didn’t comprehend. But I knew I would send kōden quickly from then on whenever the occasion arose. Ignoring what I didn’t understand wasn’t the only way to carve out my own place. Sometimes I should just serve tradition to show my respect for others.

“Finally got it?” I imagined he would say. “But don’t overdo it. Be yourself.”

Kaori, thanks again for sharing this here! And I don't think I told you—I love the pictures of your father. I definitely see you in his smiling face x

That was a great read and well written. And really relatable too, especially in regards to the work aspect, considering that we are probably just at about that turn of generations where in most fields those stable jobs that our parents had of 40 years spent in one company simply don't exist anymore- even outside of freelance work. I guess quite a few of us will have (had) to find some sort of balance between those two different outlooks at life.