Recapturing memories in a place I loved before: a fool's quest? — etc.

The digest: including postcards from KL + a letter on self-doubt and ambition + an old story about Kolkata's Chinatown + other updates.

However you found your way here, welcome! I’m Emily, and I write letters about how we seek and tell stories to make sense of a changing world and our place in it.

It’s been a while since I’ve been in your inbox. I’ve been posting letters online but I’ve not been sending them out, in case you were wondering why you haven’t received anything recently. For some reason I’ll need to grapple with soon, I’ve felt unable to hit “send” to your inboxes. It may be temporary, but I thought it best to experiment with a different way of sending you emails for now: as digests made up of individually published letters, recently published work elsewhere, writing from my archive, other people’s work, things that have nothing to do with work, and flickers of wherever I am. Hopefully, you’ll find them a mixed delight…

New letter from Nusa Penida, Bali

One question I’ve been worrying over: is it possible to travel with even middle-class comforts without feeling like one is, first and foremost, just a consumer? I had less occasion to ponder this when I was younger and more often travelling solo on a tighter budget. But now I’m wondering: Does one always have to go off the beaten track where there are fewer of the usual trappings like nice cafes and restaurants and hotels in order to feel like a “traveller”? Are there no respites to be found in travel the way most people do it? At the same time, is there anything more irritating than the tourist who thinks they aren’t a tourist, when they’re going by the same guides and recommendations as everyone else?

Stories I wrote elsewhere

For the latest issue of Mekong Review, I wrote an essay about all the river journeys I’ve taken. An excerpt:

While ambient sounds provided a soundtrack for my thoughts—in one village, it was the muezzin; in another, a neighbour partaking in a passionate karaoke session that seemed to swell the air above the open water—what kept coming back to me was the memory of entering the village of Pitas Laut, narrowing into a winding tributary under the hooded shelter of mangrove trees.

We could do so only because the water was “turned on”, as the villagers describe it in Malay, and even then we had to swap our boat for a slimmer one before we weaved between flanks of bakau kurap, an especially ubiquitous species of mangrove found here. In the rustle of the breeze, they seemed almost human to me—their roots like a dancer’s arched feet, their slim, spear-like seeds hanging from their branches like a woman’s earrings, waiting to fall off and grow new roots in the soil. From their tangled shadows we bumped up gently against a bank alongside a smattering of other moored boats, where marshy ground quickly gave way to a grassy plateau squeezed between river and sea, where this fishing community had built their wooden stilt homes.

Read the rest here. (You’ll need a Mekong Review subscription.)

For Al Jazeera, I reported a story asking the question: Can palm oil plantations play a meaningful role in wildlife conservation (and maybe tourism)?

Because of the socioeconomic benefits palm oil cultivation offers—as well as the fact that more and more wildlife is roaming in plantations—it is increasingly seen as necessary that palm oil be produced more sustainably and that agribusinesses take a more active role in conservation.

“When I first started, I always promised myself not to work with the palm oil industry. But now we cannot avoid working with them—at least for the elephants,” said Nurzhafarina Othman, the founder of the nonprofit Seratu Atai, which works with smallholders to minimise human-elephant conflict.

These animals need large areas to roam and in the last 40 years, 60 percent of natural elephant habitat in Sabah has been lost, mostly as forest is converted for agriculture.

Between 2010 and 2021, at least 200 elephants died—some of which were found to have been poisoned on or near palm oil plantations. The state authorities estimate there are fewer than 1,500 pygmy elephants left in Sabah.

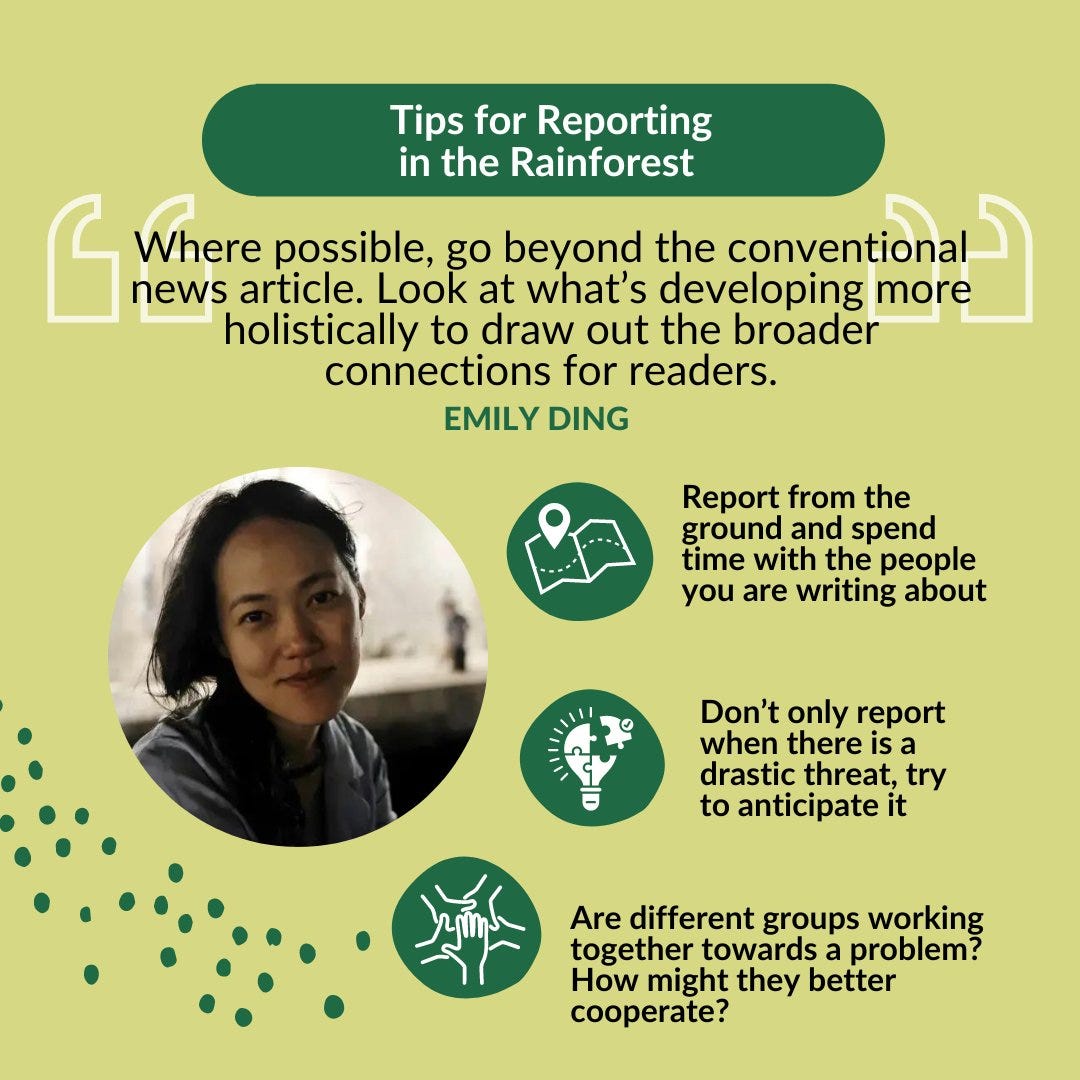

The Pulitzer Center’s Rainforest Journalism Fund, which funded this story as part of a larger project, made a Twitter—well, X—thread on the story and posted some “tips” they asked me to share, cobbled together from a short chat we had 😅

I wrote more about this project on my Mastodon thread.

On the same project, while traveling through the Lower Kinabatangan-Segama Wetlands of Sabah, Malaysian Borneo, for this story last year:

Wait, am I being served up for dinner? Do a double-take, what do you see? A mosquito net! No need for pesky ties and wall hooks, just open and close it like an umbrella. Genius! All thanks to my gracious hosts in the village of Dagat 🙏

(I’m posting more photos from the trip on Instagram.)

Something I wrote before

A young Bolivian who was working as an undocumented person in the city told me how he made ends meet working for restaurants and catering companies. Sometimes he worked in the mornings and in the evenings, and in between he couldn’t afford to spend money to make the journey home and rest. If he was lucky, he would get the occasional gig to babysit an eight-year-old boy, and the boy’s parents would give him money to take him to the cinema. There, he would be able to take a nap.

Other days, he might go to Chinatown. He had eaten there often enough and had made the acquaintance of a young Chinese waitress at a restaurant. Once, tired, he had asked her, “Do you think I could take a nap here before I go to work?” He was half jesting.

But it was that window between lunch and dinner, and there weren’t many customers around. To his surprise, she nodded and pointed him downstairs to a corner obscured with stacks of chairs.

They were just two people from different places trying to get by in a city they had dreamed of, and Chinatown was where their paths crossed.

And I leave you with

Loves chewing the corners of my books and magazines, this one. And she’s very good at looking mournful so you’ll do what she wants…

E.