How do you read and annotate?

Sometimes, I read books like it's homework—and maybe I shouldn't 😅

However you found your way here, welcome! I’m Emily, and I write letters about how we seek and tell stories to make sense of a changing world and our place in it.

I’ve been reading more books this year compared to previous years, and more intentionally—in, I guess, the spirit of wanting to learn something from them, in form or subject, and to be in conversation with them to better augment my thinking and imagining in hopes that it will all enter the metaphorical blender of my mind and churn out something sort of novel. I’m still skimming off the top of my bottomless pit of queued books, which, right now, tends to feature the books that have been long talked about that I never managed to get to, and I’m looking forward to when I start exploring more obscure and overlooked terrain.

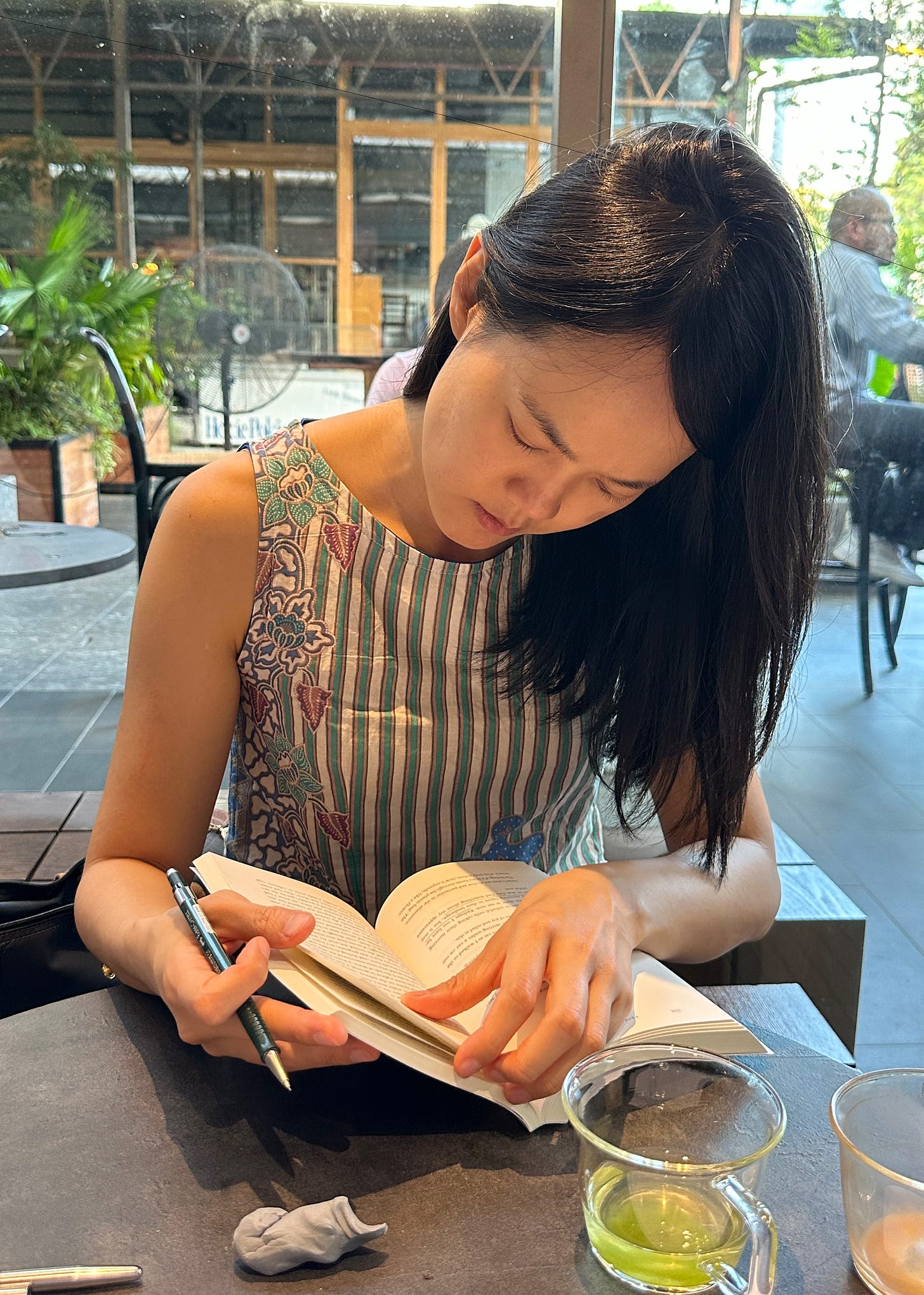

How I read these days: sitting upright at my desk at home, or at a cafe table outside, with just a mechanical pencil—0.7 2B lead tip preferable, which feels like the right amount of sootiness for me, even if it sometimes leaves imprints on the opposite page—always in hand for annotating. Occasionally, when I’m feeling tired and just need to lean back, I’ll go curl up on the sofa and just read without any pencilling at all, which is by far the cosier way to read and I definitely find myself to be more present on the page, more in the flow of the story. But then I’ll feel compelled later to go back to my desk to skim the text again and mark it where it’s called my attention. This double duty takes time, obviously, when there’s already so little time in the day, so whenever I can I opt to sit myself down straight-backed somewhere—at my home office, occasionally on the porch table outside with the dogs for company, out at a cafe—with a pencil ready in hand. In this way, reading these days feels like doing homework to me, which I mean mostly in a good way: I love homework when I’m setting the homework myself! But I do also miss just giving myself over to a well-spun tale, the way I did when I was a much younger reader.

Back then, I read everywhere: in moving cars, at the dinner table, while tailing my mum in shopping malls. Unlike other kids who maybe had, say, their video games confiscated, my mum had my books confiscated—usually when my school exams were coming around—which led to, I remember, a couple of frustrating moments when she forgot where she hid them because she’d had to get more inventive as I had found them before, in varying arrangements, in her closet, obscured by her hanging clothes. In retrospect, of course, I recognise this as funny, endearing even. I mean, my mum thought I had a reading problem 😂

But, I suspect, because of the sheer amount of information I take in, across all sorts of subjects, I forget or overlook plenty of things, or can’t immediately call something to mind when I need it—though, funnily, what I do selectively remember I seem to remember very intensely. So that’s why I document (try, anyway), well, pretty much everything, and started annotating the books I’ve read, because it’s happened before that I absolutely loved a book or a movie, could go on about how it made me feel and the general thrust of it, but somehow couldn’t tell you how it ended. Also, books help me think, and I don’t want to always have to re-read a book again to know where to look for a thought that felt generative, and that I knew I wanted to explore further. I want to be able to flip through the pages and have something jolt my mind.

I had left a draft of this letter hanging with only this same title for months, but was encouraged to finally write it when I came across Brandon Taylor’s recent Substack note on this very subject. I found much to agree with in the responses, especially one by Emily Crossen, who wrote:

I underline when moved to underline. I try not to overthink it; I want my subconscious involved. Sometimes, later, I see what I underlined and don’t know why but it’s interesting to try to reconstruct.

I had wanted to figure out a better “system” to my haphazard annotating. But then I remember that, though I get immense satisfaction from it, the act of categorising and “filing” things away for future discovery—we already need to do so much of that in the admin of our personal lives!—really bogs me down and takes up the time I could spend on more productive things, like actually writing. I don’t need the tyranny of bureaucracy.

So, here’s the simple way I’ve been annotating, and how I will continue to do it:

For books, I use only a pencil—for all my annotations, because it makes me feel more free: I don’t tend to rub things out but the possibility is there. Sometimes I use a ruler to underline, but I’ve learnt to embrace the tremulous squigliness of my lines. Spoken like a true pedant, I know.

Mainly, I underline—for all sorts of reasons (positive and negative), and I don’t distinguish between them. Maybe I like, or dislike, how a particular sentiment is expressed or just how a line is written, or I stumble on a word I don’t know or something I want to learn more about or a description that perfectly encapsulates someone I know.

Sometimes, I find myself underlining too many sentences—some books are that good or speak to me that much! I’ve learnt to just draw a vertical line in the margins to mark out those sentences or paragraphs instead.

Occasionally, I’ll write notes in the margins—sometimes it’s literally “Haha!”—but that doesn’t actually happen too often because I do like to keep my books somewhat clean, but also I don’t want to interrupt my reading too much. I tell myself that the fact of the underlines will jog the memory of my thoughts, but I’m probably overestimating myself here. I’ve definitely come across old books and wondered why I marked something 😅

I’ll asterisk or put a round orange sticker alongside paragraphs where an idea really stood out to me and I know it’s something I’ll want to come back to in the future—usually because it touches on a theme I’ve long been occupied with and want to expand on in my own work.

Sometimes, I’ll take photos of the pages with such asterisks or orange dot stickers and upload them onto a drive or cloud for when I don’t have the book with me—say when I’m in Berlin, where I only have a small library; the rest of my books are in KL—and I think I might want to refer to it or write about it.

Just last week I gave Zotero, software that can also be used online, a trial run. It helps you keep track of your references so you can better cite them after, should you ever need to. It also lets you pull from the web with a handy browser plugin. (Here’s a comparison chart between Zetero, EndNote, and Mendeley.) Until now, I’ve just been dumping everything into my iPhone’s Notes app, but I think this might be a better way. I’m still trying to decide whether it’s worthwhile to subscribe to, as I would likely need to subscribe in perpetuity once I get dependent on it!

And that’s it, really. How do you read books?

Readings, etc.

# The New Tourist by Paige McClanahan—a good read that makes an important point: though tourism can seem like a frivolous activity, its economics are anything but, and it should be reported on and written about with the same gravitas as other industries, because it is no less rapacious. This booked provoked many thoughts on a theme I’ve been thinking about. A separate letter to follow.

# I enjoyed Sally Rooney’s Intermezzo, as I had expected to—though I will say that its events unfolded predictably, if you’re already familiar with Rooney’s themes (which, by the way, I am all for). The point where it collapsed a little for me, felt almost farcical, was the part near the end where Peter Koubek’s two loves meet: not so much in terms of plot, but in terms of the execution of it—peals of laughter, eyes shining, Peter staring helplessly with happy confusion. In an earlier letter, I mentioned how much I enjoyed the short story excerpt that had been printed in The New Yorker before the book’s dissemination, about the connection that was beginning to bloom between Ivan, a twenty-something chess genius (Peter’s baby brother), and Margaret, a woman in her mid-thirties working at the arts club where he dispensed, easily, with a game. But actually, given more air in the book, this relationship felt less interesting to me in its depiction. In the tangle of relationships, the one I ultimately felt most interested in was the one between the two brothers, who have found it difficult to be close to each other in their adult lives, in part because of their clashing worldviews.

After reading this book, and thinking back on all of Rooney’s previous books, I texted a friend saying, “She seems very optimistic about what love, in whatever form, however imperfect, can do to people. It made me think she must have a great love in her life and I googled and I was right haha”:

She credits her husband, John, with making her writing possible, and not just by bringing her cups of tea and emptying the bins. “Having had this experience of falling in love when I was very young, with somebody who completely transformed my life, and transforms it every day, has allowed me to write stories about people whose lives are transformed by love,” she says. “Without that, I don’t think my work would be recognisable. Just his presence in my life made it possible for me to write everything that I’ve written.”

In this vein, here’s a thought-provoking take by Andrea Long Chu:

Over and over, Rooney’s characters put their faith in love as a means of escape from the conventional roles assigned to them by society and by each other; no sooner have they achieved this than they are rudely confronted with inequalities of wealth, status, and power that are clearly fatal to their idealism — but not to love itself. I take this to be the modest provocation of Rooney’s novels: the idea that love is real precisely because it is a product, one created by social conventions, by market forces, by systems of violence, and, behind all of this, by human beings themselves. This is not, I admit, a Marxist theory of love. It is something more unexpected: a lover’s theory of Marxism.

# Watched the Netflix documentary series Hitler and the Nazis: Evil of Trial, and it’s hard not to feel a sense that we are repeating history. The NYT’s review compares the lessons Hitler taught history in his desire to “make Germany great again” to what a Donald Trump presidency that wants to “make American great again” might set off—how no one took seriously Hitler’s proclamations, irrefutable verbally and in writing, and how one should be careful to take Donald Trump seriously despite everything that tells you, surely, you need not. But, perhaps because I am not an American, I found more echoes—if not necessarily parallels—in what Netanyahu’s administration is doing to Palestinians today. Worth watching if you didn’t grow up learning this history (in Malaysia and Southeast Asia, WWII was characterised more by the Japanese Occupation), and I liked how the narrative was framed with a foreign correspondent’s reporting and the Nuremberg trials, though I’m not sure about the character re-enactments, which felt too dramatic and repetitive.

Also read: Sidewalks by Valeria Luiselli, Miranda July’s All Fours, Zen Cho’s The Friend-zone Experiment.

Joy is not a crumb

The always satisfying mala ramen at Towzen, a vegan Japanese restaurant in Kuala Lumpur—the first farflung outpost of the associated Kyoto establishment, founded twenty years ago 💚

And I leave you with

Some of the permanent residents of a community garden in my city, which was turned into a lively makeshift bar on a day I visited.

From KL,

E.