Amanda Lee Koe: "I was not wrong, I was only in the wrong time and place"

Q&A: A Singaporean author on her debut novel, growing up under the influence of cultures not rooted in her own reality, and how she built her own.

A jolt of jazz

I loved Amanda Lee Koe’s debut short story collection, Ministry of Moral Panic, when I read it a few years ago. She’s a brilliant stylist, her voice a jolt of jazz: completely alive on the page, always a hint of mutiny in even the most down-and-out characters.

So I was excited about reading her debut novel, Delayed Rays of a Star, and having a chat with her about it for Electric Literature. We ended up talking about many things: the multitudes we all contain, the blurred lines between art and life, how and where we find our most “authentic” selves.

In truth, in asking Koe about her experience, I was also exploring ideas I’ve been thinking about that I think she expresses really well in her published writings and on Instagram—growing up in places like Singapore and Malaysia under the influence of cultures not rooted in one’s own reality, how that shapes one’s identity, and how one might convey that to the rest of the world, to be better seen.

Seeing as all that’s completely in line with this newsletter, I’m reposting our conversation here, with an additional back-and-forth that was left out of the published version. I daresay you’ll find something in it you’ll connect to.

Republished from Electric Literature:

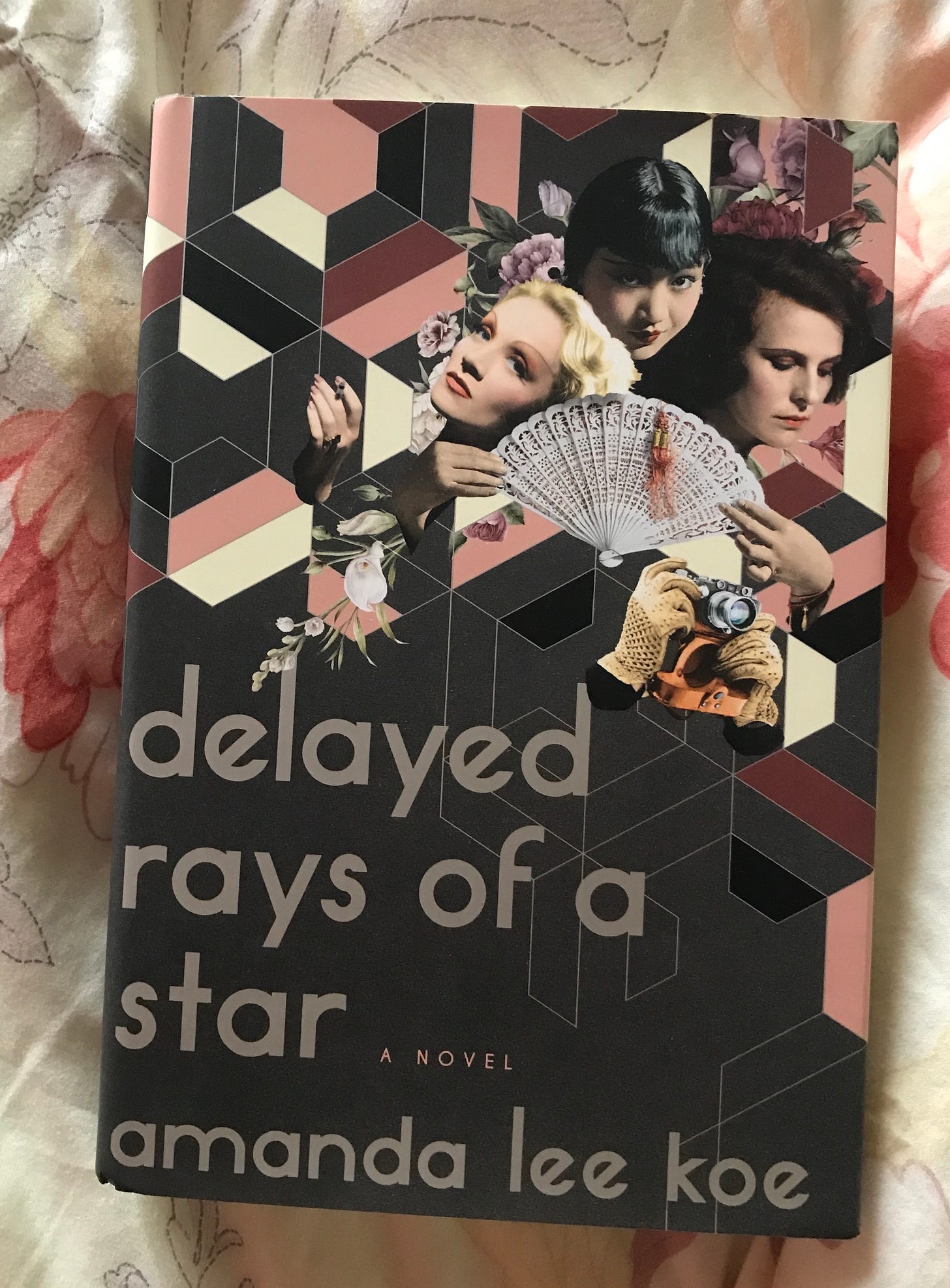

In 1928, at a glamorous soirée in Berlin, the photographer Alfred Eisenstaedt takes a black-and-white photograph of Marlene Dietrich, Anna May Wong, and Leni Riefenstahl, immortalising the three actors before the height of their fame. This brief, shining moment, where the women’s lives intersect, is where Singaporean author Amanda Lee Koe begins her sweeping, richly imagined debut novel Delayed Rays of a Star.

Spanning eras and geographies, from Weimar Berlin to Los Angeles Chinatown to the Bavarian Alps and modern-day Paris, through the rise of Hitler and World War II: Delayed Rays of a Star follows the three women as they move through the world in their different ways, in pursuit of art, ambition, fame, and love, while navigating thorny issues of identity, ego, and integrity in turbulent times. They all want to be, as Leni expressed in the book, “the reason for things.”

And evolving around them, sometimes intertwined with them, are a secondary cast of characters. Among them, a Chinese housemaid beginning to intuit the ways of a woman of the world, a German-Turkish-Kurdish young man struggling with his multiple identities, and a German soldier on leave from North Africa grappling with a secret love. Amanda Lee Koe brings each of them to life in deeply specific, textured detail, so that their dreams are no less bright, and their desires no less fervent. Like the three actors, they’re feeling around, sometimes blindly, for a heightened existence.

I’d enjoyed Amanda Lee Koe’s debut short story collection, Ministry of Moral Panic, which made her the youngest person to win the Singapore Literature Prize in 2014, at the age of twenty-seven. And in a way, her debut novel also feels like a tapestry of short stories, with a dazzling rolodex of characters, including cameos by J.F.K, Davie Bowie, and Hitler. In her hands, even in a pithy exchange between two people, you can sense their burgeoning humanity, the multitudes they contain.

Emily Ding: First, let’s talk about that photograph. What about it captured your imagination? What drew you so completely into this world?

Amanda Lee Koe: It was a photograph that was so unlikely, one that opened up many questions. To see pre-Hollywood makeover Marlene, early flapper-styled Anna May, and pre-Nazi propaganda Leni together, it was like a Pandora’s box.

Not just as a writer but as a person, I’m always looking for the intimate gap in history, the lateral wormhole in time. These were three women who would soon all be pioneers in their own ways; here they were at a party, being coy for a man’s camera. If you know Marlene at all, you’ll know that once she became that blonde femme fatale we all know her to be, she wouldn’t be caught dead smiling so sincerely and guilelessly for the camera. Once she had her star image in place, it was something she was very aware of performing for the camera.

Marlene meant a lot to a younger, half-formed version of me. I grew up with a gigantic poster of her on my wall, and I think in some invisible, personal way, she must have helped me to grow into the adult I wanted to be. So I guess it’s fitting that, eventually, I somehow managed to create an aesthetic universe that was capacious enough for her to exist in.

ED: What did she mean to the half-formed version of you?

ALK: As a teenager in socially conservative Singapore, I had no epoch-appropriate idols, but Marlene was someone I had chosen out of time and space because she gave no fucks, was so publicly bisexual, knew how to work a pair of pants the same way she knew how to work a dress. I never got to see any of that. I grew up with literally zero visible queer role models, to the point that I thought oh, maybe there were no gay grownups in Singapore. From the age of 13 to 16, I was in an all-girls school, and they sent me to corrective counseling when they found out I had a girlfriend. To remember that Marlene was so free and unapologetic decades ago made me feel that I could not only survive, but laugh my way through whatever I was going through.

And it wasn’t just Marlene either, it was the whole milieu I became enchanted by. At 19, I felt a great affinity for Dada, Surrealism, even tried to study German as an elective language. But after three levels, my school didn’t offer anything higher than that, so I’m still stuck at toddler vocab probably. Eventually, as with all idols, I forgot about Marlene, or rather, she became dormant in my life with the passage of time, and I hardly thought back about her at all. When I came upon that Eisenstaedt photo of the three of them in 2014, the year I moved to New York, it was like seeing an old friend again.

ED: A central theme of your book and the thing that ties most of your characters together—including the more minor ones that revolve around the three women—is that they have dual/secret selves, and there are schisms between their inner and outer lives. This usually poses the question of authenticity, but you have the Hollywood director Josef von Sternberg, a creative and romantic partner of Marlene’s, speaking of a “lust for bothness,” and I’m struck by what you have Anna May thinking, about “living truthfully under imaginary circumstances.” Can you speak to this a bit more?

ALK: A commitment to duplicity, or multiplicity, is a form of authenticity too. Anyone who’s a whole human being, who’s being honest about their humanness, will be able to locate this sort of breach between their inner and outer selves. It could be a small rift or a large one. By way of a simple example, people are often surprised to learn that I’m an introvert, because I am not at all shy; in fact, I am quite bold. But this constant tussle—any tussle between two seeming opposites—this lack of holistic consistency, is what’s specific and truthful about being human, is what leaves room for fictional characters to evolve in a way that isn’t programmatic.

“Living truthfully under imaginary circumstances” is actually something I picked up in an acting class. The only time I got stuck in the writing of this novel, I took an eight-week seminar at an actors’ studio in Manhattan focusing on Meisner, Strasberg and Hagen to try to understand that process more for my characters who were professional actresses.

ED: Something else I’m thinking about after reading your book is how a more interconnected world lets us try out new identities: We’re permitted to be different people in different places, or, even if we don’t end up somewhere else, to think about ourselves as someone from a different place. This sort of internal freedom seems especially true for Bébé, the Chinese immigrant housemaid—I love Bébé as a character, by the way! (Note: You can read a longer excerpt about Bébé at Granta.)

ALK: Everyone loves Bébé! Have you seen the Hou Hsiao Hsien film Millennium Mambo? With Bébé, I was partially trying to capture the innate innocence of Shu Qi’s character in Millennium Mambo, who has been through a lot, but has such purity in her reaction to seeing snow for the first time.

ED: Yes, but along with that purity, there is a delicious sort of creeping knowingness too? I especially liked the part where, when questioned by a French immigration officer, Bébé repeats a story a blacklisted Chinese publisher had told her about young Chinese peasant women reading Madame Bovary underground and took it as her own. What I liked about it, I think, was that it suddenly hinted at depths and complexities you might not have associated immediately with her, and also, I think it’s a testament to the power of ideas—how one, seemingly innocuous little thing revealed to you can change how you think about the world, yourself, and your place in it.

ALK: That’s one of my favorite bits of the book as well. I had a friend, a Chinese political scientist, who was a boy during the Cultural Revolution, and he told me many things that gave me deep insights into China’s modern history. I think the tendency is for a lot of Anglophone writers to approach the traumatic parts of Chinese history with a Western liberal lens, and I was interested in trying to show something else. This episode, with Bébé using Madame Bovary and the Tiananmen crackdown essentially to commit asylum fraud for personal rather than political reasons, was a wink at acknowledging the existence thereof, but also reversing the latent cultural superiority inherent in the ways “third-world” migrants and refugees tend to get written and thought about, as if they can only suffer, as if they can’t scheme and dream just like everyone else, too. The part where the French lawyer tears up and says: “I can’t imagine they read Madame Bovary in China” still cracks me up. And the best thing is that this was historically factual, too. Bourgeois European novels in translation, which had been banned by the Communist party, were all the rage amongst literate Chinese youth. I just nudged the historicity a little further.

ED: We were talking about the freedom of trying out new identities. Do you think a person has any obligations to their “origins”?

ALK: I think the question about obligations and origins is one that needs to be reconsidered in our globalized, wired age: What are origins, in the first place? So often this gets conflated as place of birth, or color of skin, but what does that really mean today? For example, I might be racially read as Chinese, but what does that even mean in my middle-class, Anglophone context, where my first language is English, and I grew up reading Virginia Woolf?

The assumptions that we might make are natural, but they’re also limited by a failure of imagination. Most readers might be likely to assume that I identify most with Bébé or Anna May in the novel, because I’m Asian and female. But what if, in fact, the character I personally most identify with might actually be Josef [von Sternberg]? The bit where he goes off on a tangent about code-switching depending on whether he’s in Europe or America was a bit of a hehehe for me.

The idea of personal reinvention, liminal identities, and its linkage to the ever-changing metropolis, is of great importance to me. Particularly perhaps because I grew up in Singapore, which is less than two-thirds the size of New York City (the city, not the state!) but is its own country. This is like growing up in a big city that is also a small town. Infrastructurally and economically we are a big city; socially and emotionally we are pretty much a small town. In a small town, it’s harder to evolve, to try on new behaviors and identities that might be more intrinsically in line with who you know or want or have gradually or suddenly discovered yourself to be, because you’re hemmed in by the cultural context, the class bracket, the social norms you were born into, and expected to perform within.

ED: It sounds like you had discovered for yourself an eclectic range of influences, a whole different other world, to fill in the gaps of what you were feeling while growing up in Singapore.

ALK: I was someone who really did not fit into the Singaporean education system, and I had a lot of free time because I hardly ever did any homework. I only did my homework if I had a crush on the teacher! Because nothing felt like a good fit, I had to learn to build my own private universe from scratch to feel like it was worth my while to wake up, go to bed, on repeat. Autodidactism is fantastic because it is so bespoke.

I’m sure that I projected a lot of my own baseless fantasies onto Weimar Berlin, but as a teenager growing up in a repressive culture where there’s so little pushback from the populace, the mirage of the famed sexual freedom and decadent amorality of Weimar Berlin was like a mirage of an oasis in the desert for me. Didn’t matter if it was real or not, I just needed it to go on.

Because I didn’t ever feel like I belonged in contemporary Singapore, because in my formative years people were always telling me I was wrong, or abnormal, or that I had to change, I think that to stay alive on the inside, I needed very deeply to believe that I was not wrong, I was only in the wrong time and place. That there would have been a space and time in which I would have felt at home. In which I would have been right, for once.

ED: Though much of your novel is set in previous decades, it also feels very current at the same time, and resounds, I think, with our present anxieties about gender and race and representation, and moral responsibility. Was this something you set out to explore with your novel?

ALK: The funny thing is that when I first started on this novel, people thought it was an obscure, historical anomaly that would appeal only to a niche audience. That was pre #MeToo, pre-Trump, pre-Crazy Rich Asians, pre-mainstreaming of female empowerment (of course I believe in actual, intersectional female empowerment, but also a lot of the real issue around gender equality is now being used as a marketing sideshow), pre-Lucy Liu getting her very well-deserved star on the walk of fame. But when it came out that my manuscript got sold before I graduated, then the same people who’d written me off as an experimental nutcase writing myself into a niche started saying I was a trendy writer with commercial appeal. Neither of these contexts and characterizations has anything to do with me and why I write, so they didn’t affect the vision I had for the work.

Race, gender, and representation are issues that I think all good artists today deal with, in one way or another, some more personally than others, some more covertly than others, but I do think that there are traces of the anxieties of every generation that occur congenitally within our collective work. The challenge, I think, is to not have a didactic approach, and to not overthink the relation—if it’s there in you, it will appear on its own in the work; and if it isn’t in you, it’ll never be there, or it’ll smell phony if you force it.

ED: You’ve spoken about your dilemma of choosing a voice performer with an appropriate accent for your audiobook, and how you settled for a “Midatlantic” sound. How did you create the right tone for the novel in order to inhabit all the different characters and eras and milieus, but that could still feel specific to each character? Like when Bébé described one man’s ass cleft as “the color of unhulled beansprouts”!

ALK: I might have a certain disadvantage that’s also a happy advantage, which is that although I’m a native English speaker (we were schooled in English in Singapore, Mandarin is a second language) from a former British colony, the syntax and idioms I grew up with have absolutely nothing to do with English, or even Germanic or Romance languages. My syntax and idioms come instead from a messy broth of Singlish (Singaporean English), Mandarin, Chinese dialects, and assorted Southeast Asian polyglossia (I can speak market Malay). And I love it, I love every last weird noun and sound of how that has turned out for me. Love isn’t a word I’d use lightly.

What I realized was that I didn’t want to lose the spirit of the polyglossia I am used to, even though obviously I was writing in English, and also that the tone shouldn’t have to be a slave to an era or character or milieu, because then I would be locked into just one thing, and I wouldn’t be able to be ambidextrous or polyamorous enough to tell the story—the stories—I wanted to tell. I just had to find a tone that reflected the newness of my physical millennial shell and the mental octogenarian oldness that lives inside.

ED: On your Instagram account, you sometimes make up stories about imaginary characters—basically yourself in different guises (this caption made me laugh, because I feel like I must know an aunty like that!)—that are often funny and moving. What’s the impulse behind that?

ALK: Hahaha I can’t believe someone would notice that and think to ask this question! Now that I’m looking through my feed, it’s true, those characters do crop up more regularly than I thought. To be honest, I have no idea what drives that impulse, it’s so throwaway for me, I’m just having fun, being frivolous, but if I had to guess, perhaps a strong sense of play, and wanting to be many things at once?

Play is super important to me. So much of writing is being able to play well on the page. When I was nine, as the oldest sister to two malleable toddlers, I used to dress them up as wuxia characters, and we would go on adventures together… Monkey God, Dongfang Bubai, the Eight Immortals… I was always the lead character, not just because I was the bossy eldest child, but also because these adventures actually had contiguous plots from day to day, and the lead character is the one who shapes the action. There’s huge craft and technique to good playing.

And, it’s something we all knew how to do once! I think it’s a huge shame that playing and imagining were driven out of most of us with conventional modes of learning, just because it can’t be quantified and tested as useful. I hated the rote education I received and rebelled against it in the smallest and stupidest of ways—too many ear piercings, spelling my name backwards, arguing for Mercutio as the most interesting character in Romeo and Juliet when we were supposed to write an essay on oxymorons—because I needed to show myself that I was still alive in this fucking bog. And then what? Finally you get out of school, where they tried to beat all the play out of you, then you start hearing the sort of language the corporate marketplace is using, that co-opts playing and now places a premium on it: “Sandboxing,” “thinking out of the box,” whatever. I spit on their graves.

ED: In your novel, it seems that to live fully, one has to live on a heightened plane—the antidote of the line you have one character say about Ingrid Bergman: “She’s too real.” And I’m thinking of what Marlene asks herself: “What was her magic? And where did it live?”

ALK: It’s funny but Ingrid Bergman says in an Ingmar Bergman film, I think it was Autumn Sonata: “I could always live in my art, but not in my life.”

To be honest, and it sounds so terrible to admit this, but before I started to write seriously, I didn’t really care if I lived or died. Sure, I was curious about the process, but I wasn’t that invested in the outcome. I used to lead a more impulsive, thrill-seeking life, I went down shady alleys, made the most impractical plans, had disastrous love affairs, took strangers up on weird propositions.

But ever since I found I could write, I’ve led a much calmer, quieter life. I need things to be peaceful in my life now, so I can be disciplined in the work that is required for a sustained form like the novel. Making bad decisions in my life was just a way to see what would happen next. Looking back now, I feel like it was not propelled by “self-destructive behavior”, but by something more unknowable that I would call narrative hunger. Surely I can’t be alone in feeling this; there must be others out there with the same impulse. And because I didn’t have literature then, I thought I had to live it out.

Now, however, I get to bring that narrativity, that hunger, to the page from the safety of me being alone in my pajamas at my desk! So in the midst of this physical comfort, I try to remind myself to honor the philosophical sense of that mental risk: Don’t take shortcuts. Don’t go for the schematic interpretation. Don’t believe that something can’t happen just because it isn’t conventionally done.

Should you read it?

All things considered, when paced and savored—and there are many lines to savor—Delayed Rays of a Star is a slinky, moving, and funny read about complicated women and complicated people who, well, want unapologetically. The writing is confident and brilliant, and the characters indelible—each interaction between them revealing something profound about our individual complexities.

And like its characters, it’s an ambitious book, and I’m very much looking forward to Koe’s future work. It’s also an example of what’s possible when a writer is liberated from feeling that they need to hew to their own culture, history, and geography (which doesn’t mean they’re any less connected to it), so that they may choose to write “capaciously” enough, as Koe says, to encompass many worlds at once. It feels like a kind of permission.

Granted, it sometimes feels a little too enamored of the real lives it’s based on, unable to relinquish facts more fantastic than fiction that don’t always move the narrative—though, I have to say, I didn’t mind this so much since it’s something I’m very sympathetic to. In its voracity the book does sometimes feel too sprawling, with many narrative strands competing for primacy. But I started to think of the book less as a “novel” per se than as a lively tapestry of stories.

So, yes, read it, and take your time 🩵

I leave you with…

The places we make & the places that make us

Back when I was in my twenties, I cooked lunch in a bakery and restaurant in an island town. It was a summer-tourist place, but we were open year-round. Especially in winter, after the noontime rush died down, I used to stand at the door to the dining room and listen to the voices of customers troubling things out or talking town politics, going over finances or gossiping, creating their own psalm. It was the blend of voices blooming and falling that I loved, the music of a break in the day. Believing that I had a small part in making that sound possible helped me stick to the job.

—Jane Brox, A Social—and Personal—History of Silence

A ballad of the human heart

Don José, watching his son toast the houses he would build for Peru's homeless, watching his son tremble with emotion at the warmth of the family surrounding him, recognized that Fernando's heart was like his own: nostalgic but combative, caring but suspicious, able to bundle great ideas into intractable knots of personal anxiety. It is the way men begin to carry the world with them, the way they become responsible for it, not through their minds, but through their hearts.

—Daniel Alarcón, War by Candlelight

The world we live in

This dramatic photo feature by James Whitlow Delano on the dystopian reality of gold mining in the highest permanent human settlement in the world—La Rinconada, Peru—reminded me of this William Finnegan story, which remains one of my favorite nonfiction pieces.

William Langewiesche, apparently a respected aviation writer, argues that, actually, MH370 isn’t really the mystery everyone thinks it is—in a piece that’s narratively strong and ostensibly persuasive. I was ready to believe it. Then came this rebuttal. Guess the verdict’s still out.

Wesley Morris, a self-described “single black gay man”, charts the evolution of romantic comedies and what it says about us, and argues for their comeback, as “the only genre committed to letting relatively ordinary people—no capes, no spaceships, no infinite sequels—figure out how to deal meaningfully with another human being.”

From the new U.K.-based Tortoise Media (the latest champion of slow journalism), a fascinating profile by Nicky Woolf: “8chan is a monster, but its creator had no idea what it would become. He was just a kid.”

Since Chernobyl’s now on the travel radar, thanks to the HBO series, here’s a beautifully written, very atmospheric, very surprising piece I remember by Henry Shukman: “It's not just the forest that's come back but all its creatures. It's the land of Baba Yaga, the old witch of Russian folktales. Is this the world before humanity? Or after? Is there a difference?”

Watch Vice’s Isobel Yeung—who has enviable lady swagger—go undercover as a travel blogger in Xinjiang, which mandated her riding camels and flashing peace signs. She’s gotten some flak from some journalists for stretching ethical boundaries; but equally, other journalists, as well as Uighur activists, have come to her defense.

Stranger Things is back. I’ve never played Dungeons and Dragons, but I have friends who take it very seriously. This is for them: The Rise of the Professional Dungeon Master by Mary Pilon.

An incredibly moving essay from historian Jill Lepore about being a mother and a writer, and the bonds between women. “My best friend left her laptop to me in her will. Twenty years later, I turned it on and began my inquest.”

An uplifting story by Mary Hui on Hong Kong’s domestic workers who “squeeze in training runs before the crack of dawn or late at night, and find creative ways to turn their household duties into training opportunities”.

On the heels of neighborly spats like this, here’s a detailed New Naratif piece comparing hawker food and culture in Malaysia and Singapore. (I had actually pitched the same idea to another food publication, but they didn’t bite!)

Words to live by

An unwelcome consequence of living in a world where everything is “easy” is that the only skill that matters is the ability to multitask. At the extreme, we don’t actually do anything; we only arrange what will be done, which is a flimsy basis for a life.

—Tim Wu, The Tyranny of Convenience

Until the next,

E.