Mike Fu: "You can be both as much as you want"

Q&A: An Asian American translator on dual identities, bridging cultures through translation, and a years-long quest to translate Sanmao into English.

Living with duality

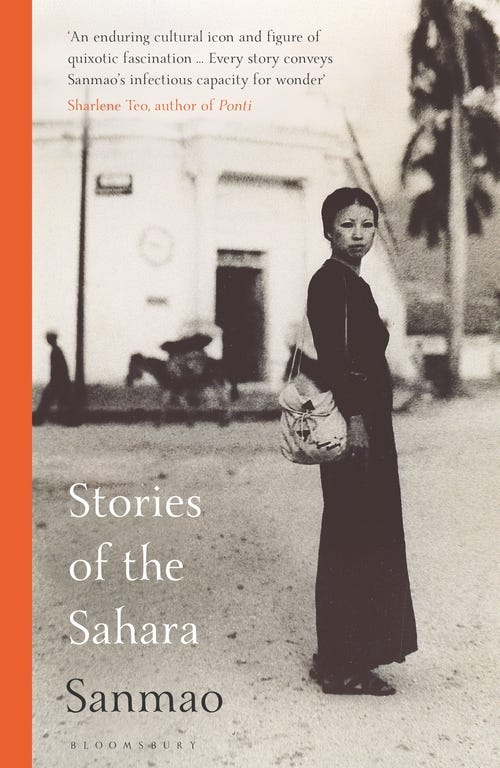

At about the time I was writing my review essay on Stories of the Sahara by Sanmao—the late Taiwanese writer who is something of a legend in Taiwan, Hong Kong, and China; recently introduced to the English-speaking world—for The Mekong Review, I had decided to begin a series of conversations about place and identity with a roster of friends and strangers on Movable Worlds. And I thought Mike Fu, a Chinese American writer and editor who translated Sanmao’s collection into English for the first time, would be a great person to kick it off.

When we spoke about a month ago, he was staying in Maryland, U.S.A., with his sister-in-law’s family, having found himself in a transitional limbo, his plans for the year delayed by the pandemic. He had decided to leave New York after spending a dozen or so years there and was supposed to head to Japan in April to start a Ph.D. in cultural studies in Tokyo. With any luck, he’ll finally make it there in the coming month.

Over the phone, we spoke about the places he has inhabited and how they have shaped his life, and how his work as a translator fits into all of it. Part of what I also hope to do with these conversations is to invite people to share how they’ve found ways to live a life that bridges multiple cultures, and with Mike, we talked about how he found his way into translating his first book-length work. We also had an interesting email exchange, parts of which I’ve included here, about some of the old controversies around Sanmao regarding the truth of her stories, and whether that matters. And before you go, make sure to scroll right down for some film and book recommendations from Mike himself.

Though this is the first conversation I’ve initiated intentionally for this newsletter, I’ve been talking with people about place and identity for a while—through casual conversations with strangers, and through the stories I’ve written for publication elsewhere. You can read transcripts of my conversations with Amanda Lee Koe, the author of Delayed Rays of a Star, and Jason Brooke, a sixth-generation descendent of the “White Rajahs”—and how Singapore and Sarawak have shaped them, respectively.

Thanks again, Mike, for kicking this off!

The Q&A

Emily Ding: So, let’s start with the cultural backgrounds you bring to your translation of Sanmao’s Stories of the Sahara. Have America and China been the main influences in your life?

Mike Fu: Yeah, definitely. I was born in China in Hubei province—actually right outside Wuhan, where the coronavirus originated. Pretty much my entire extended family, apart from a few stray relatives in Denmark, are still in Wuhan.

In the mid-eighties, my father was getting his Ph.D. in engineering in Denmark, and my parents lived there for a time. I joined them in Denmark briefly when I was four years old, and then we emigrated to the U.S. when I was five. Since then—this was thirty years ago—I’ve been living in the U.S., more or less, and as a kid, I acculturated pretty quickly.

Nonetheless, I experienced a certain bifurcation of cultures. As a Chinese American, I went to a Chinese-language school on the weekend, like most other peers of my demographic. You know, you learn Chinese for a couple of hours every Saturday and that’s it. It was something I never felt a great deal of passion for and honestly would rather have skipped. But in retrospect, it laid the foundation for my having some Chinese language capacity later on in life. Mandarin was my first language, but because I moved to the U.S. at a young age I quickly learned English and it became my dominant tongue.

ED: Where have you lived in the U.S.?

MF: We moved quite a bit, and my experience of Chinese American identity also shifted from place to place.

From elementary school to early middle school, I lived in pretty diverse metropolitan areas near NYC and Baltimore—in the suburbs, for sure, but places where there were plenty of Asians and Black people and Jewish people, and I never really thought twice about being a minority.

And then, when I was twelve, we moved to suburban Ohio, outside Cleveland, and there I was almost always the only person of Chinese descent in the room. It was where I had my first encounters with actual racism. And I think it really burst my bubble, disrupting this sort of utopian vision of America and its benign, all-embracing multiculturalism that I maybe had internalized as a middle-class immigrant kid.

I moved to Los Angeles for my undergrad, and that was also a brand new beginning. I studied film and French, and it was through cinema—not ashamed to say Wong Kar Wai especially, but also Fifth Generation filmmakers like Chen Kaige and the like—and literature in translation that I really started to become more introspective about my own background and upbringing, and about Chinese culture and language in general. I wanted to recover that part of myself.

ED: We can all relate to coming to a culture again or a new one through art. What do you think you saw in Chinese film and literature that drew you to want to reacquaint yourself with the culture? I’m thinking of a passage from an Alasdair Gray book along the lines of how, if a place has never been imagined by anybody, say an artist, then not even the inhabitants live there imaginatively…

MF: Hmm, I guess I discovered the depths of my ignorance, really. I realized I knew little to nothing about Chinese history. And I came to recognize how much that history had impacted my own family and my grandparents’ and my parents’ generations. For me, accessing those narratives felt key to accessing myself. I felt like I had to understand my context in some way. The Chinese language is my conduit to a primordial self, reaching back to my earliest memories, to a place and time before I even became myself.

Another reason I became interested in relearning Chinese was that my parents had returned to China in 2001. My father had a career opportunity back in the motherland—the hai gui [“sea turtles”] thing, right? Many Chinese of my parents’ generation who had gone abroad for education and established their livelihoods in Europe or the U.S. ended up repatriating for the career prospects and booming economy of China around the turn of the millennium. They moved back when I was in high school, and I suddenly became this young kid living more or less on his own in America. Then, each year for the holidays, I would make the long journey to visit China myself.

There were many things about those visits that unsettled me and surfaced a lot of questions for me. At first, I wasn’t so thrilled with the idea of having to go back to China so regularly and really confront that part of my identity. But as I grew into adulthood, those trips became an opportunity and also a test, I guess, of my language ability and my intercultural fluency and whatnot. I failed miserably early on. I’ve made considerable gains in the years since.

ED: What kinds of things exactly were you forced to confront?

MF: It’s not necessarily that there were aspects of Chinese culture that discomforted me. But when I was living in a very white suburban environment, in late middle school and high school, I had completely turned my back on anything Chinese out of self-preservation, sadly. I remember feeling a great deal of shame over being Chinese, by heritage. I was embarrassed to admit that I had been born in China.

It was the typical teenage impulse, compounded by being in small-town America, which created this desire to homogenize myself with the others around me, which, in my case, were all white. There was definitely a cultural flattening of the different types of backgrounds my classmates had. I wasn’t very interested in China or Chinese-ness in general, and more or less denied or rejected this fundamental part of my identity.

ED: You talked about wanting to integrate yourself with your teenage peers. Was that something you did fairly easily?

MF: Yes and no. For a while, I did want to be like everyone at school. I quite literally wished I hadn’t been born Chinese. Then at some point in high school, I transitioned to the opposite impulse, thinking, Well, since I am the only East Asian person here—there were a handful of South Asian students and maybe one Black kid out of a class of 325 or so—if I’m going to be different, I can show them how different I can be.

Luckily, I found some really good friends who were instrumental in helping me find different modes of self-expression. I fell in with a certain crowd that was into, let’s say, alternative, heavier music. For a while I was one of the kids who wore black band t-shirts all the time, I had spiky blue hair, things like that.

ED: How would you compare your adulthood and adolescence in the U.S.?

MF: So I lived in L.A. from age eighteen to twenty-two. Then I moved to New York right after that, from 2008 up until June this year. I think they are both really amazing and wonderful cities. I have a great fondness in my heart for L.A. and I feel like it’s misunderstood and unfairly dismissed by many; it’s not as easily accessible as New York in some ways.

I came of age in L.A. and really discovered my tribe and was able to plant the seeds of my own creative life, my interest in language and storytelling, in college there. But New York, where I did my master’s, is definitely where I became more grounded in myself. If L.A. is where I started on this journey of self-discovery, then New York is the place that allowed me to embrace myself fully and become more rooted and confident, both in myself and in terms of my career and creative ambitions.

ED: I’m guessing you see having a dual identity as a useful expansiveness rather than a feeling of being “less than” either way…

MF: Yeah. As a Chinese American, or any person of dual identity, I don’t think you’re bound to be half-this, half-that, or that you have to allocate a certain percentage of your identity or selfhood to either side. Rather, you can be both as much as you want, and it gives you the capacity to choose, which is exciting and liberating.

ED: We’ve talked about some of the downsides. Have there been ways in which you felt your dual identities worked in your favor?

MF: To be honest, I appreciate the anonymity I feel in Asian countries and contexts nowadays. It wasn’t always like this. When I visited China as a young adult, people could peg me as Other from a mile away based on appearance alone—body language, clothing, and so on, before I even opened my mouth. Nowadays there’s such incredible mobility for younger Chinese, between their homeland and the West, broadly speaking. There’s a whole spectrum of transnational experience, and all of it is far more ubiquitous than it once was. I’m delighted to lean into this ambiguity. Nobody bats an eye at me anymore. Sometimes they do squint a little and ask if I’m from Hong Kong or Taiwan. “But you don’t sound like a person from Hubei,” they’ll say, confused.

ED: Going back to the times you went back to visit China, how long were these trips? Were they formative?

MF: I went back for the first time when I was nine years old, and then again when I was fifteen. Since age seventeen—right after my parents repatriated—I’ve been going about once or twice a year. But barring one summer in grad school, when I spent three months studying at Soochow University, my trips have always lasted only about two weeks or so. I’ve even grown accustomed to the incredibly long flights, which I used to hate.

I’m just now transitioning out of a full-time career in university administration. After graduating from Columbia in 2010, I worked for over a decade in academia—first at Columbia, the past 7.5 years at Parsons School of Design. So despite my family being back in China, three months is the longest I’ve been able to spend as an adult in a Chinese-speaking environment.

I’m mildly self-conscious about my not having lived in a Chinese-speaking environment since my days in Suzhou; sometimes I feel a bit of impostor syndrome when it comes to translation. As a heritage speaker but also someone of the diaspora, I can be a tad insecure, at times, about my own shortcomings, blind spots, or areas of inexperience when it comes to language. I am who I am, though, and I want to embrace this fully. I know I put in the work with all my projects.

It’s something I’ve been thinking about how to articulate. We tend to think of translators as a discrete group but, in my mind, the word “translator” can denote a whole range of archetypes of people with different levels of cultural and linguistic fluency. I think there’s a huge disparity—not saying that’s a bad thing—and overall, this diversity of experiences that we bring to translation makes the field dynamic and interesting.

ED: Actually, how did you get into translation work in the first place?

MF: I got into translation while I was completing my master’s in East Asian languages and cultures. I moved to New York to pursue this M.A. program at Columbia, and during that time my focus was actually Chinese cinema. I didn’t have a clear sense of my academic interests then, but it was a stepping stone. It was really during this first round of grad school that I managed to recultivate my Chinese language ability.

Between my first and second years of grad school, I participated in a program sponsored by the U.S. government. It’s called the Critical Language Scholarship and it’s run by the U.S. Department of State. The ostensible aim is to encourage American citizens to improve their abilities in a certain set of languages deemed critical to national security. So that’s a pretty intense framing of it, and I think it usually draws students of international relations and political science, those types of majors and backgrounds. But I was grateful to receive the scholarship and spend the summer studying Chinese in Suzhou. Conveniently enough, my parents were in Shanghai at the time, so I was able to go visit them on the weekend occasionally.

As for translation, I started doing it informally through a couple of different avenues, both in and out of the classroom, and began picking up freelance projects. For a while, I interned with dGenerate Films, a distributor of independent Chinese cinema, and through them, I got to know a number of filmmakers in China. Eventually, I translated some of their screenplays and film treatments, or helped to subtitle their feature work, that kind of thing.

ED: What was your time in Suzhou like? Did you ever experience a reverse culture shock of sorts? Did anything surprise you?

MF: Suzhou was a really special time for me. I remember writing a lot about it back in the day—they’re private blogs now. Something about being in China made me realize a couple of things.

No matter how frustrating things were—I’m talking, I guess, about general cultural differences or things that may not be as palatable to a Western or non-Chinese traveler, maybe a certain brashness or type of behavior in public, some of the bad stereotypes—I found that I had in myself an endless reserve of patience because I felt empathy and a genuine sense of belonging in some way.

Even as a Chinese American almost twenty years removed at that point—maybe because my parents were living in Shanghai, and maybe because the rest of my family have always been in China for the most part—I really had the feeling that, These are my people. And although I hold an American passport, I think in many ways, back then and even now, I do consider myself Chinese and that doesn’t necessarily need to be at odds with my citizenship or other markers of my identity, which can all feel a bit arbitrary. My Chinese-ness is an integral and indelible part of me, no matter how much I didn’t want to accept this in high school. It’s an ongoing journey to embrace and articulate what it means to be both Chinese and American in this day and age.

And I want to throw out there too that a lot of this was shaped also by the period of time I spent studying abroad in France as an undergrad. At the time I had a pretty good command of the French language and was able to speak it more fluently than some of my classmates who were white. But in Paris, I had the feeling that no matter how well I spoke French or how I wanted to present myself culturally, no matter how I dressed, or whatever my French accent sounded like, I was without a doubt received not as an American but a Chinese person. That was very frustrating for me, at times, but also provocative.

I thought, I guess I am a Chinese person at the end of the day. I won’t deny that part of myself. But in France, it was made apparent to me—similar to when I was in Ohio as a teenager—that the first thing people perceived of me was my external appearance, and they had assumptions about me based on that appearance.

ED: Would you say your parents were already quite cosmopolitan and well-traveled and more familiar with other cultures, and that they passed that on to you? Or did it mostly start with you?

MF: Yes and no. They had their time in Europe in the eighties, which wasn’t uncommon. There were a lot of Chinese students in that decade who were supported by the Chinese government to go abroad. I think my parents are, at heart, very proud to be Chinese, and I say that looking back and recognizing that they really only lived in the U.S. for a little over a decade before going back to China. So, of my family, I’m the person who spent the longest amount of time in the West. And because they’ve been back in China since 2001, they feel very rooted in and familiar with Chinese society.

Both sides of my family are from the same town in central China, and my parents grew up in the sixties, and in a very provincial and self-enclosed kind of world. So their initial stint abroad was the beginning of something very new for us all, and certainly has shaped my life in profound ways. Still, I feel very much connected to my origins. I go to Wuhan almost yearly. My father had a hardscrabble rural upbringing but was able to change his life through his persistent effort and gaining access to education. It’s a remarkable and yet ordinary story, typical of tens of millions of their generation.

ED: Sanmao’s Stories of the Sahara is your first book-length translation. How did you come to translate it?

MF: My friend, an American who was living in Beijing, gave me Sanmao’s book as a present for my 26th birthday. I took it with me on the subway every day and just found myself really drawn in by her writing. I felt an instinctive bond; it was deeply moving. I’d read things in Chinese throughout grad school and had dabbled here and there reading modern literature, but I think her work held my attention in a way that I was pleasantly surprised by. I became interested in translating it and was shocked to discover that it hadn’t been done before. That basically set me on a years-long quest figuring out how to go about doing it.

I started working on translating the book as a side project, during my MFA in fiction, which I began in 2012, just for the sake of doing it. I was very curious to see how it would turn out. I found it very fun and engaging. It was a couple of years later through a Taiwanese friend of mine that I was introduced to an agent in Taiwan, who would later come to represent Sanmao’s estate. We were corresponding by email, and sometime later he asked if he could use some of the chapters I had translated to pitch the book to English-language publishers. Of course, I happily agreed. After that, Bloomsbury bought the rights to the book. They asked me to translate another excerpt for evaluation. I was formally hired for the project in 2016.

ED: What was the experience of translating Stories of the Sahara? Perhaps not so much the technical aspects, but more the emotional aspects. What excited you about it? Did it help you explore certain questions you were living yourself?

MF: It was an intensive and thrilling project to work on. You know, I had read the book a couple of times and I felt a strong emotional connection to Sanmao, both the writer and the persona she represents in the stories.

In particular, I’m thinking of the story “Hitchhikers”, which closes on a very meditative note:

Day after day, I drive along the one tarmac road in this wilderness as usual. At first glance, it looks totally deserted, devoid of life, without joy or sorrow. In reality, it’s just like any other street or tiny alley or mountain stream in this world, carrying the stories of its passers-by who come and go, crossing the slow river of time.

The people and moments I encounter on this road are normal as anything that anyone walking on the street might see. There’s really no greater meaning to it, nor is it worth recording. But Buddha says: “It takes a hundred years of self-cultivation to be in the same boat, and a thousand years if you want to share the same pillow.’ All those hands that I’ve shaken, all those brilliant smiles exchanged, all those boring conversations, how could I just let a wind blow through my skirt and scatter these people into nothingness and indifference?

There are a few moments throughout the book where she expresses a quiet wonder about life, both its resilience and fragility. These passages were what initially gripped me when reading it in Chinese. That she chose to end her life a decade and a half later lent an acute poignancy to my working on these passages in the translation.

ED: In translating this book, you were bridging not just one culture, but two—or three, it could be said: Chinese, Spanish, and Sahrawi. What was it like to not only be translating Sanmao’s experience as an ethnic Chinese, but also how she as a Chinese sees and experiences other cultures? Did you bring parts of yourself into this process, and if so, which parts? How did you go about it?

MF: Sanmao’s self-understanding seems very much to be rooted in a mythic Chinese identity that she references consistently and casually, despite having grown up largely in Taiwan. I suppose this wasn’t uncommon in her day, especially for people of her background who had emigrated to Taiwan in the late forties. In the external world of the Spanish Sahara, she operates as a kind of a proto-manic pixie dream girl, the charming but mysterious “Oriental” woman who has free agency to do or say as she pleases. To her Chinese language audience, she adopts a nearly confessional tone and holds the reader close to her interior tribulations or musings. At this point in her life, she had already lived in or traveled through Western Europe and the United States, before ending up in Africa. Beneath the playfulness of many of her stories, there’s an underlying loneliness—and perhaps this is something I could understand intuitively.

ED: I had emailed you while writing my essay, asking you for clarification on whether Stories of the Sahara is part fiction. The book itself is silent on this, and most secondary sources seem vague on the matter. I only realized it wasn’t strictly a memoir when I read the chapter “Crying Camels”, marveling at how Sanmao had found herself in the thick of things—meeting Bassiri, a real-life Sahrawi guerrilla leader, and witnessing his lover’s lynching. Then I googled him and realized he had disappeared years before she placed him in her timeline.

MF: I think there are some deliberate ambiguities regarding Sanmao and the veracity of her tales. While she, the writer, no doubt lived in the Spanish Sahara in the 1970s, the persona she assumes under the guise of “Sanmao” (rather than Echo, the name by which she was known to José and all others in real life) seems to have experienced a range of colorful and dramatic events that one could consider embellishment, if not outright fiction.

From 1976 onwards, she was this literary superstar and very active in the cultural sphere in Taiwan as a writer, translator, and film scriptwriter—basically a cultural guru, all the time using this moniker “Sanmao” [translates to “Three Hairs”, as in, on a head; or “Thirty Cents”], which is a kind of a funny little name and a nod to a 1930s cartoon strip. I think because of her fame and this pseudonym she used, at a certain point she began to attract people who were suspicious of her identity and the truth behind her experiences.

Sanmao garnered her fair share of skeptics or detractors who not only questioned the premises of some of these stories but even accused her of larger lies, i.e. never living in the Sahara, fabricating her relationship with José, things in that vein. For example, one writer called Ma Zhongxin wrote a whole book about going out to Western Sahara, basically trying to retrace her footsteps and debunking what she seemed to put forward as truth. And it seems to be the Saharan period that people tended to fixate on.

Personally, I think she took creative liberties with the stories that she originally wrote for consumption in Taiwan. I don’t find it compelling or productive to parse exactly what is truth versus fiction in her work, although some people—even recent readers of my translation—have apparently taken issue with this. Curious to hear what your feelings are on this matter.

ED: Thanks for clarifying. That explains the ambiguities, not just in the book but in what’s been written about it.

For myself, I think a collection of writing inspired by place that is a mix of fact and fiction can work really well. I’m thinking, most recently, of Flights by Olga Tokarczuk. I’ve also continued to enjoy travel memoirs later found to be embellished, like John Steinbeck’s Travels with Charley, for their literary value. I do think that imagined experiences in a place based on what one knows can be as revealing and true about a place as experiences that actually happened.

Still, and this may be the nonfiction writer in me, I think it can be helpful to know before I begin a book if it’s not entirely nonfiction in instances when one might have a reasonable expectation that it would be, though I agree it’s not necessary to know which parts exactly are imagined. I think it just determines the lens with which one begins a book, and it can be jarring to have to switch the lens halfway through.

With Stories of the Sahara, I did come to it with the expectation that it was a memoir, because much of what has been written about it in the English-language media—which was how I first found out about Sanmao; I can speak but no longer read or write Chinese—don’t mention otherwise. At the same time, she’s been defined as an Asian woman ahead of her time traveling the world, and since that’s what Stories of the Sahara is about, I guess it added to that expectation.

MF: I understand what you mean about switching lenses as a reader, depending on the genre you believe a book to be. I guess Sanmao eludes easy categorization here. I’ve described Stories of the Sahara as “semi-autobiographical” in passing, but I wouldn't want to be the one to draw a line in the sand and vouch for her experiences. My impression is that the content of her later books was not as contested as Stories of the Sahara. Perhaps readers and critics are—subconsciously or not—searching for authenticity when it comes to the consumption of narratives about “exotic” locales, in particular.

Mike’s three things

ED: To wrap this up, I’d like to ask you for a few commendations… A book of Chinese literature translated into English?

MF: Karen S. Kingsbury’s translation of Love in a Fallen City by Eileen Chang was an old favorite of mine in grad school, beautifully and seamlessly rendered.

ED: A Chinese film?

MF: So many to choose from! I might recommend two early directorial works by Jiang Wen: In the Heat of the Sun (1993) or Devils on the Doorstep (2000). Jiang is known mostly as an actor, but I think both of these films—which take very different styles to address two fraught historical eras, the Cultural Revolution and the Sino-Japanese War—are so masterful and splendid.

ED: A place you love?

MF: I’m pining for New York these days, in my not-quite-Tokyo moment. I miss going for a jog in Brooklyn, particularly this loop eastward from Clinton Hill, my former neighborhood, into Bed-Stuy and then back. I miss the independent cinema Metrograph, nearby favorite restaurants like Wu’s Wonton King, and Chinatown in general. I miss bars, period.

To more illuminating conversations,

E.